by Dr. L. LaSimba M. Gray Jr.

In spite of the pathos of segregation, there were some benefits for African Americans. Segregation created the “crucible of necessity.”

A crucible – in its classic sense – is a vessel used to melt materials at a high temperature for the purpose of purification. Gold is purified in a crucible. Crucible also means a severe trial – and that’s my focus.

Segregation was the period in history that made clear to African Americans: “You may be physically free but your freedom has social and economic lim- itations.”

African Americans realized the limitations set by segregation in every aspect of life. It determined where African Americans could live, eat, recreate, shop and work.

And, it set up dual systems of compensation. African Americans could work side-by-side with European Americans for less in wages and without benefits. Wisdom teaches that as long as you can tolerate evil you will never change the evil.

Out of necessity

Segregation prevented access to capital without repercussions. Out of necessity, men such as A.G. Gaston of Birmingham began to create businesses to serve the needs of the African-American community.

“Every time I went into a business to make money, I lost money; but every time I went into business to meet a need, I made money,” Gaston said.

In 1909, out of necessity, Dr. C. A. Terrell and the Negro Baptist Association founded Jane Terrell Hospital in Memphis for African Americans. At the time, African Americans were being mistreated throughout the health care industry. By the mid-1920s, 75 percent of African-American registered nurses working for the Shelby County Health Department were graduates of the Terrell Hospital School of Nursing.

The necessity of countering the negative portrayal of African Americans in media owned and controlled by European Americans drove P. Hamilton to pub- lish “The Bright Side of Memphis” in 1909. African Americans typically were presented as shiftless, irresponsible, lazy and dangerous to society.

“This book is to record the achievements of the thousands of honest, law abiding, industrious colored citizens of Memphis,” Hamilton declared.

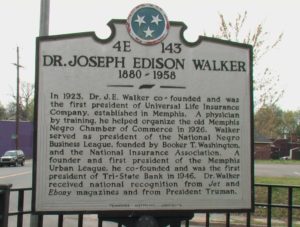

In 1924, Dr. Joseph E. Walker – with accumulated and organized capital from African Americans – founded Universal Life Insurance Company in Memphis. Repeatedly encountering customers living in sub-standard houses, Walker learned that in many instances the customers were renters. Or, they were not able to secure loans to make repairs.

In 1924, Dr. Joseph E. Walker – with accumulated and organized capital from African Americans – founded Universal Life Insurance Company in Memphis. Repeatedly encountering customers living in sub-standard houses, Walker learned that in many instances the customers were renters. Or, they were not able to secure loans to make repairs.

Out of necessity, Walker organized Tri-State Bank, with the grand opening on Dec. 16, 1946. African Americans from all over the Mid-South made deposits and loans. A way had been made for African Americans to secure loans to repair their homes, purchase automobiles and homes and send their children to colleges and universities.

In the early 1950s – and, again, out of necessity – Walker developed the Dr. J.E. Walker Homes subdivision in south- west Shelby County. African Americans took great pride in living there. They had access to their own shopping center, historical T.O. Fuller State Park, churches, schools and businesses owned by Afri- can Americans.

G.P. Hamilton reported that in 1909 African Americans in Memphis owned 27 restaurants and cafes, 10 plumbing companies, 39 professional plumbers, 22 moving vans, a seminary, a hospital and a medical school. Countless small businesses were doing business for the community at-large and African Americans in particular.

The big question

What happened after desegregation?

I pondered this mind-blowing phenomenon for years, concluding that there are missing links between the end of segregation and the integration of society.

Integration provided African Americans with new choices that slowly destroyed the crucible of necessity.

Prior to the end of legal segregation, LeMoyne College had a long waiting list and could be highly selective with student admissions. Desegregation opened doors at the University of Memphis, Rhodes College, Christian Brothers University and the University of Tennessee. Today, LeMoyne-Owen College must recruit with great intensity.

The missing links are affirmation and transformation of thinking.

African Americans were not given the benefits of psychological intervention in the aftermath of slavery. No considerations were given to the dire need to reconnect the emancipated Africans to their culture and the motherland: Afri- ca. No other ethnic group in this country needed such reconnection because no other group had been as systematically disconnected from its culture.

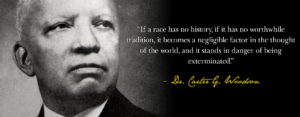

Dr. Carter G. Woodson talks about this systematic disconnection in “The Mis-Education of the Negro.” African Americans were educated in a European model to mirror our European brothers and sisters. Many schools developed for African-Americans were labeled “normal” institutes. African-Americans were not taught about Africa and the rich history of the continent where humanity was created and civilization was begun.

Dr. Carter G. Woodson talks about this systematic disconnection in “The Mis-Education of the Negro.” African Americans were educated in a European model to mirror our European brothers and sisters. Many schools developed for African-Americans were labeled “normal” institutes. African-Americans were not taught about Africa and the rich history of the continent where humanity was created and civilization was begun.

The reconnection to Africa is powerful and, regrettably, feared by many. So much so that in 1978, Zbignew Brzezinski, national advisor on security to Presi- dent Jimmy Carter, wrote memo-46. Allowing African Americans to connect with African leaders was not in the best security interest of America, he wrote.

I read that memo and resolved to make that connection. In the reconnection, there is affirmation and transformation of personhood. In that reconnection there is a connection to the greatness and richness of Africa. The entire world needs Africa to function. Without Africa and her rich mineral deposits, the industrial world would have to shut down.

To overcome the results of brainwashing and the disconnection from our culture and native land, we as African Americans must affirm systematically who we are without shame and apology.

In affirming, we must teach our youth to respect self and others, be responsi- ble for all decisions, strive for greatness and to be creative and industrious for the good of others. Such teaching transforms the thinking. Take it from the apostle Paul: “Be not conformed to this world but be ye transformed by the renewing of your mind.”

The vehicle

I remain convinced that Dr. Maulana Karenga gave us the most affective vehicle in 1966 when he presented the concept of Kwanzaa as a celebration for African Americans to reconnect to African culture and values, and to transform our thinking.

Kwanzaa is a seven-day festival centered on the Nguzo Saba (seven principles). The principles are: Umoja (unity), Kujichagulia (self determination), Ujima (collective work and responsibility), Ujamaa (cooperative economics), Nia (purpose), Kuumba (creativity) and Imani (faith).

Each day is centered on a principle. The celebration is punctuated with music, fellowship, dance, poetry, narratives, African attire and African food.

Thanks largely to the late Adjua Naantaanbuu, Memphis has benefitted from the public celebrations of Kwanzaa. I am convinced that it is time to move to the vital level of institutionalizing Kwanzaa in family settings.

Start with dinner. Have all family members gather and discuss the seven Kwanzaa principles. Conduct table catechisms on current issues in this coun- try, the world and Africa. Challenge each family member to explain how he/ she plans to implement the principles in every day living. Ask each member how he/she plans to honor God, serve others and enjoy life.

The benefit is that when ethnic groups celebrate their culture, they develop appreciation for themselves and others. They learn to celebrate diversity and the collective contributions of other ethnic groups.

And they celebratively chime in “me too.”

(This is one in a series of periodic columns by the Rev. Dr. L. LaSimba M. Gray Jr., pastor emeritus of New Sardis Missionary Baptist Church.)