by Dr. L. LaSimba M. Gray Jr.

Special to The New Tri-State Defender

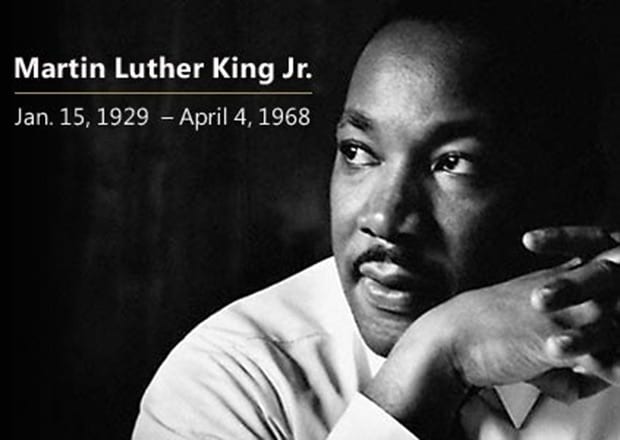

Dr. Martin L. King Jr. demonstrated courage on a daily basis because of his moral convictions. Dr. King was willing to stand alone when he felt strongly about a strategy or position in the civil rights movement.

When the civil rights movement shifted to the human rights movement in the 1960s, Dr. King stood in opposition to his staff, supporters and close advisors on the question of the Vietnam War.

On April 4, 1967, while attending a meeting of the “clergy and laity concerned” at Riverside Baptist Church in New York, he denounced the war – a move many view as tantamount to nailing the top to his own casket.

“My conscience leaves me no choice,” said King in response to the pushback from civil rights collaborators.

The year 1968 was a tumultuous year of volatility and change. The peace movement and the presidential election dominated the news. The peace protest challenged the civil rights movement for media coverage. Dr. King joined the peace movement and vowed to defeat President Lyndon Johnson and all candidates who supported the Vietnam War.

Meanwhile down in “ole Memphis Town,” a local labor dispute intensified between the city administration and the sanitation workers, who were subjected to the most unsanitary conditions. They were required to empty 55-gallon barrels of garbage by hand and to carry on their shoulders garbage in tubs that leaked slimy filth over their clothing.

The way these men smelled at the end of a day’s work prompted some to refer to them as “walking buzzards.” Unlike their white coworkers, there were no showers for them and they had to board public transportation or walk home. Whenever weather conditions prevented work, the African-American workers were sent home without pay while their Caucasian counterparts remained on the clock.

And, they were paid less in wages.

The straw that broke the back of tolerance happened on Feb. 1, 1968, when two sanitation workers, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, sought refuge from the rain in the back of a garbage compactor. The compactor malfunctioned, crushing them to death. The robust, pipe-smoking T.O. Jones, a former sanitation worker who had keyed the organization of local 1733 of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), decided enough was enough and called a meeting of the workers.

On Feb. 12, 1968, 700 of the 1,300 workers refused to report to work. Garbage began to pile up on city streets by the tons. By spring, mass meetings, protest marches, press conferences, police confrontations and a defiant mayor dominated the local news.

The citizens of Memphis wanted their garbage picked up. Mayor Henry Loeb’s telephone rang without ceasing as did the phones of members of the city council. When Loeb refused to negotiate with the mostly black workforce, a labor dispute became a racial crisis.

The Memphis Branch NAACP executive committee adopted a resolution supporting the striking workers and local African-American churches joined the movement. Concerned citizens, led by the Rev. James Lawson, organized Citizens on the Move for Equality (C.O.M.E.). The groups combined forces with influential Caucasian clergy to meet with Loeb and appeal to members of the city council.

AFSCME dispatched a representative to Memphis to assist the sanitation workers. Jones now had professional labor experts with experience in negotiating and settling labor disputes.

The Rev. James Lawson, an ally of Dr. King, invited him to Memphis. The invitation was extended with Dr. King in the midst of planning the Poor People’s Campaign and wrestling with dwindling financial resources because of his aggressive anti-war stance.

With his staff voicing the belief that visiting Memphis was a distraction, Dr. King responded, “Nonviolence is on trial in Memphis and I must go.” His decision to join the sanitation workers married the civil rights movement to the labor movement and a local labor dispute became a national concern.

After repeated failures to settle the strike with Loeb, the strategy shifted to the city council. Councilman Fred Davis Jr. urged the city council to get involved and hosted a private meeting at his home in Orange Mound.

In that meeting, as reported by Jerred Blanchard, a Caucasian member of the city council, “We had a substantial majority that agreed to recognize the union, give the workers an increase in pay and allow (union) dues check off through the City of Memphis Credit Union.”

Blanchard expressed utter disgust when the private vote was never transformed into a public vote at City Hall. Seven of the Caucasian council members could not bring themselves to cast the vote to end the strike and erase the necessity of Dr. King returning to Memphis.

One week later, Dr. King, 39, was assassinated on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel.

From a Birmingham jail cell, Dr. King once wrote, “The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in time of comfort and convenience but where he stands in time of challenge and controversy.”

The seven Caucasian City Council members who voted against recognizing the union decided not to stand up for the least, the last and the neglected of our society. They were not willing to risk their power and prestige to end a long dark night in Memphis history.

The Rev. Dr. James L. Netters, a member of that 1968 City Council, lamented during the MLK50 commemoration that, “We had settled the strike.”

A public vote to affirm the private vote would have saved Memphis from the dubious distinction of being the city where the prophet of peace, Dr. Martin L. King Jr., was assassinated.