Dr. Willie W. Herenton was the 28-year-old principal of Larose Elementary School – 38126 in South Memphis – when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. came to the city in support of striking sanitation workers in 1968.

The youngest principal in the Memphis City Schools system at the time, Herenton recalls that “the white leadership had identified me as a bright and shining star.” So, it was no wonder that he was summoned to the superintendent’s office after pictures were published of him protesting in front of City Hall.

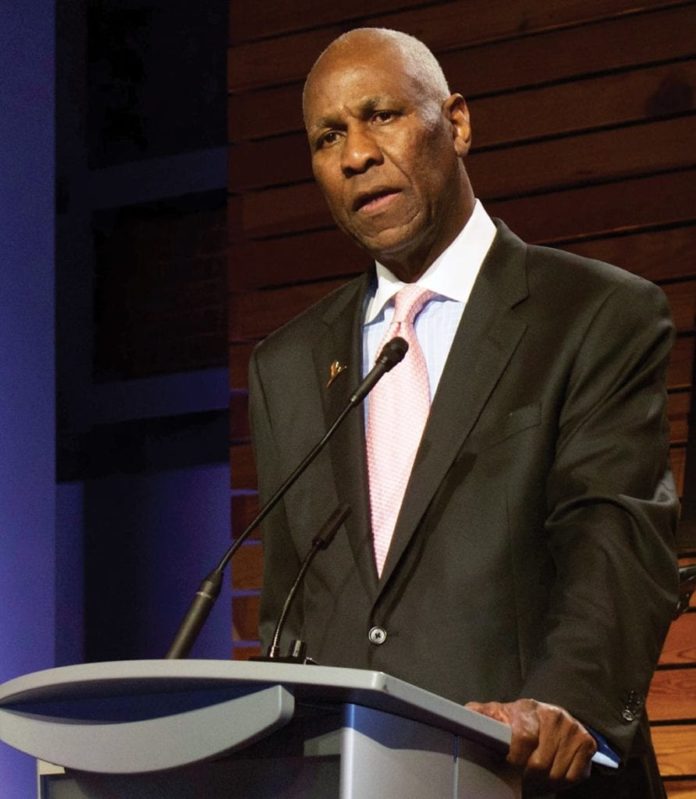

Herenton’s account of the experience was interwoven into observations he made on Feb. 27 at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. The task of making a special presentation to five of the surviving strikers drove Herenton – Memphis’ longest serving mayor and the first African American elected to the position – to his knees in a bow of reverence.

That evening’s salute came 26 days after a ceremony in East Memphis near Colonial and Verne marked the 50th year after two sanitation workers – Echol Cole and Robert Walker – had been crushed to death in the back of a garbage truck. They had climbed into the vehicle seeking refuge from the rain.

The deaths sparked the sanitation workers’ strike.

It was, said Dr. Herenton, a “garbage strike …it smelled bad. Your working conditions were horrible. The vehicles were not safe…”

“I vividly remember participating in both of the marches. I remember standing in front of City Hall wearing a sign – ‘I AM A MAN’.”

Why was it important for black men to wear such a sign?

“In Memphis, during that dark period of our history, men of color were not considered to be men who deserved dignity and respect as a human being.”

The garbage strike revealed inhumanity, he said.

Twenty-four years later, Dr. Herenton entered the mayor’s office and sat at the same desk that Henry Loeb sat at as mayor in 1968. “The same one that he had the shotgun under the desk, the same office that Rabbi (James) Wax, Bishop (Carroll T.) Dozier, Henry Starks – a number of very passionate preachers – had appealed to this mayor to be humane to these sanitation workers.”

The rest is history, Herenton said, recounting the Rev. James Lawson asking Dr. King to come to Memphis.

“All of a sudden this strong movement came up and I had to look myself in the mirror. I said, ‘Should I be comfortable?’ I was making $32,000 a year. That was a lot of money. I had two kids…and I was married. I had put my job on the line. …

“Transformation from a boy to a man, that’s what Dr. King did for me. Because when I looked in the mirror I had to make a decision. Was I going to be a boy or a man?”

He recalled mean policemen who “wanted a riot to break out” and the commitment of labor leader Jesse Epps of the American Federation of State County and Municipal Employees. And he remembered people beginning to respect the garbage workers who withheld their services.

Meanwhile, garbage piled up, rodents multiplied and Loeb continued as a recalcitrant mayor. “But still we made it.”

The five sanitation workers honored that evening were among hundreds who “demonstrated the strength of conviction, tenacity, perseverance,” Herenton said.

Pausing before calling the men to the stage, Herenton then added this:

“Because Dr. King came to Memphis and he gave his life here in Memphis, we ought to have more black men who would refuse to bow to injustice, to the lack of diversity…That’s what Dr. King gave me; a conversion from boyhood to manhood. So don’t let his dream die. We’ve still got work to do.”