On July 1, 1917, a car full of white men drove into East St. Louis, Ill., and opened fire, shooting into homes while black men, women and children slept in their beds.

Troubled by this assault on their humanity, black citizens took up arms just in case these “joy riders” returned. Not long after, white, plainclothes police officers, unrelated to the earlier incident, drove into the community in an unmarked car and behaved in what witnesses would later say was a “suspicious manner.” Thinking these police officers to be the same men who had driven through the community earlier, black citizens opened fire upon the car, killing two detectives.

The next day, the bullet-ridden, bloodstained car from the night before was parked in front of the police station in plain view of passersby. White citizens, shocked by the sight of the vehicle, vowed revenge. They armed themselves, gathered in mobs at the intersection of Broadway and Collinsville in downtown East St. Louis, and began their reign of terror by stopping cars driven by black folks and shooting the inhabitants execution style.

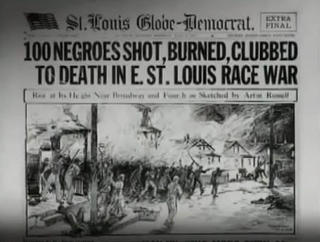

Over the course of the next day, black men, women and children were killed indiscriminately. Men were lynched; women were thrown off bridges; children were thrown into fires.

Entertainer Josephine Baker, then an 11-year-old girl living in St. Louis, called the scene “apocalyptic” and said it was a major reason she would leave the United States. Jazz trumpeter Miles Davis, who lived in East St. Louis for five years of his life, said in his autobiography that stories of what happened that day had a “negative effect upon his view of white people.”

Over $400,000 of property damage was sustained, and while the official report put the number of those killed at 39, W.E.B. Du Bois, who was sent in to write about what he called “The Massacre of East St. Louis” by the NAACP, estimated that as many as 200 were killed.

“The worst thing we can do is ignore this place,” said Southern Illinois University-Edwardsville professor Andrew Theising while discussing the riot with St. Louis Public Radio. “How can we ever think of fixing the problems in our cities if we don’t understand where they came from … if we don’t understand that they exist?”

This begs the question: Why were so many murdered, and why does no one seem to remember?

Many blacks left the South during the Great Migration of the early 20th century. They moved North in an attempt to escape the horrific conditions of life forced upon them by the explicitly racist power structure in Southern states. When they moved North, they discovered that racism was not just in the states that left the Union to form the Confederacy.

The arrival of black workers from the South angered many whites, and the citizens in the city of East St. Louis, just across the Mississippi River from St. Louis, were no different. For years, tensions simmered between the black and white communities of that municipality, and on the night of July 1, 1917, things came to a tipping point.

Ironically (or perhaps appropriately, given the nature of white supremacy in America), more black folks were arrested for this incident than white. In all, nine whites and 12 blacks were convicted for crimes related to the massacre. The absurdity of this fact led a congressman who investigated the incident and its aftermath to say, “It doesn’t appear that you can convict a white man of anything that happened here on July 2, 1917.”

We need to remember what happened in East St. Louis.

We must remember because while many paint black folks as having a pathological predisposition to engage in riotous activity, the vast majority of “race riots” in the United States are, in fact, race massacres that were committed by white people against innocent black Americans.

It is important to remember that—in the early 20th century—communities in the North, Midwest and West were just as invested in racial violence and white supremacy as communities in the South. As black folks fled subjugation in one part of America, mass violence against burgeoning black communities was a key feature of the white reaction to this influx of refugees fleeing racial oppression. Part of the reason race riots were so prevalent in the early 20th century was the economic anxiety of white Northerners confronted by a new black workforce that was willing to work for less in an attempt to establish roots in a new town.

It is this same white “economic anxiety” that was partly responsible for giving us a racist, misogynist 45th president. If Americans were better students of history, they would have been better prepared for the “whitelash” to black achievement that happened on Nov. 7, 2016.

We must teach the totality of American history—not just those things that paint the country in a good light. People need to know that there is a dark side to this democratic experiment. One that black folks know too well.

We have a movement raising awareness of black folks who have been murdered at the hands of the state because their lives matter to us. Those killed in East St. Louis matter as well.

We need to remember what happened on July 2, 1917. We say, retroactively, that black lives do not matter when we participate an act of forgetting.