Editor’s Note: This column was originally published in May 2020, when Ida B. Wells was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for Journalism.

As an African-American journalist born and raised in Holly Springs, Miss., you’d think I’d have known more about my hometown’s favorite daughter growing up. But I didn’t.

Then again, I guess it’s not so surprising that I didn’t know much about Ida B. Wells-Barnett. It’s not like any Mississippi public school was teaching much black history in general, let alone lionizing an African American – a woman, no less – who stood up against racial violence in the Deep South.

The history we got was around the lives of people like George Washington Carver, W.E.B. DuBois, Booker T. Washington and, of course, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. As far as women were concerned, the go-to was Harriet Tubman, for obvious reasons. Names like Fannie Lou Hamer, Madame C.J. Walker and Ida B. Wells usually got a vague sentence or two — which is no way to even begin to acknowledge what Wells’ life was about, the impact that she had.

But Wells’ contributions were given their due earlier this week. On Monday (May4), Wells became a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, receiving a special citation from the selection committee. The honor comes more than 130 years after the lynching of a close friend launched her into becoming one of America’s first investigative journalists.

“That is such an amazing honor,” said Wells’ great-granddaughter Michelle Duster, in a video statement. “She spent her life sacrificing to tell the truth regarding lynching during her time.”

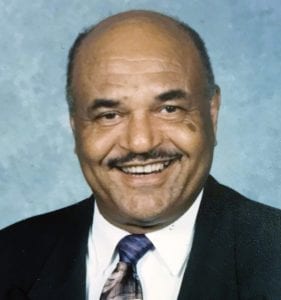

Like I said, I didn’t learn any of this in school. Like African-American parents have done for generations, it was my father, Eddie Lee Smith Jr., who taught me about the woman I respectfully and reverently now refer to as my “homegirl.” And those lessons took the form of places I could visit, and people I could meet.

My dad has his own corner of history as the first African-American mayor of Holly Springs. It was during his third term in the late 1990s that he learned that Jim Wells, Ida’s father, worked as an apprentice carpenter on the Spires-Bolling House on North Randolph St. It was on that property that Ida B. Wells was born on July 16, 1862.

And as far as my dad was concerned, that made it a historic site. He worked to get the city to acquire the Spires-Bolling House, then leased it to what was originally the Ida B. Wells-Barnett Family Art Gallery (Now the Ida B. Wells-Barnett Museum) for $1. Like both of my parents, she also attended Rust College (then Shaw University), though she was reportedly expelled after starting a dispute with the university president.

My dad died in 2001. And in the years since his passing, my family’s ties to Ida B. Wells, the museum and her family have only grown. For years, the museum has hosted an annual celebration of Wells’ birthday, including a banquet that brings her descendants from Chicago and elsewhere to Holly Springs. I’ve attended that banquet many times, even providing videography a time or two.

I’ve had several conversations with her great-granddaughter Michelle Duster, who is an author in her own right. And I’m proud to be able to call Dan Duster, Wells’ great grandson, my brother in Alpha Phi Alpha.

And after all of that, you might think I learned more about WHY her work mattered, but I didn’t. Once again, maybe that’s not surprising, considering that America wasn’t at all comfortable talking about the horrors of lynching (and still isn’t). I knew who Ida B. Wells was and where she was from – but for me, truly connecting the dots wouldn’t happen until January 2019. And I wasn’t even looking for her when I found her.

I was researching our TSDtv series, History: Hidden in Plain Sight, when I learned of The People’s Grocery, and how a dispute among children escalated into a gunfight, and ultimately the lynching of Thomas Moss, the African-American owner of People’s Grocery – and a close friend of Wells. It was his murder, along with his associates Calvin McDowell and Will Stewart, that launched her on her journey as an investigative journalist.

The narrative that white supremacists used to justify the institution of lynching was that black men were raping white women. And in the absence of good reporting, that narrative might have stuck. But Wells traveled the south, documenting lynchings, talking to witnesses and reporting her findings to the American people. “The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them,” Wells said.

“It was a very brutal, violent practice and most of the people who committed these types of crimes were never brought to justice,” Michelle Duster said. “She made a whole lot of sacrifices, but she never gave up. And she left a document, a trail of firsthand information about what was going on in our country for so many years after the Civil War ended.

“I’m sure that future generations, current generations can all be inspired and learn from what she did.”

It really can’t be overstated how dangerous this was for her. Of course, she received death threats. Arsonists actually did come for her in 1892, burning down the offices of her newspaper, The Memphis Free Speech, but she was out of town in Philadelphia. She never returned south, settling in Chicago with her husband Ferdinand Barnett, whom she married in 1895.

Many historical entries about Wells, maybe even most of them, refer to her as an “activist.” But the more I learn about her, the more I think of my “homegirl” as the pioneering journalist she was — showing WHY the press matters in the life of a democracy.

Hopefully, the Pulitzer means the rest of the world will think of her that way too.

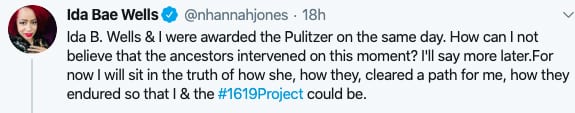

From Pulitzer Prize winner Hannah Nikole Jones: