By Marc J. Spears, The Undefeated

Editor’s Note: The following first appeared on ESPN’s The Undefeated.

Rasheed Hazzard gave up $800 and two game tickets in exchange for the prized NBA jersey last year. It wasn’t for an old Michael Jordan, LeBron James, Magic Johnson or Stephen Curry jersey. It was his late father’s game-worn jersey with the name “Abdul-Rahman” on the back, which was priceless to his Islamic faith family.

“Anything I can get that my father actually wore is special to me,” Hazzard told The Undefeated. “I bought the actual game-worn jersey with ‘Abdul-Rahman’ on it.”

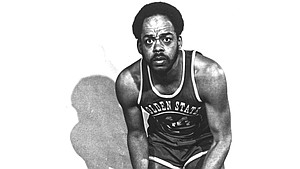

The then-New York Knicks assistant coach’s father is more well-known as Walt Hazzard, the former UCLA star guard and head coach. The 1968 NBA All-Star changed his name to Mahdi Abdul-Rahman after he converted to Islam in the early 1970s. The vintage Golden State Warriors jersey from the 1972-73 season had the No. 44 and Abdul-Rahman on the back.

Once Rasheed Hazzard finally got the jersey in the mail, he was moved to tears.

“That jersey is my prized possession at this point. I love anything that can connect me to him and make me feel like he’s there,” Rasheed Hazzard said. “It was just something not only for me, I felt like I had to have it for my family, especially for my nephews, my nieces who didn’t meet him or didn’t get to know him like that … That jersey has to be in our family.”

Walter Raphael Hazzard was born on April 15, 1942, in Wilmington, Delaware. He starred on UCLA’s first national championship team in 1964 under legendary coach John Wooden. The two-time All-America selection was also the 1964 NCAA Most Outstanding Player of the Final Four. The 6-foot-2 guard won a gold medal with USA Basketball during the 1964 Olympics and played 10 seasons in the NBA with the Warriors, Los Angeles Lakers, Buffalo Braves, Seattle SuperSonics and Atlanta Hawks.

Walt Hazzard ranked among the NBA’s top 10 leaders in assists during six seasons. The ball-handling specialist also averaged a career-high 23.9 points per game for the Sonics during the 1967-68 season.

“He played hard and hustled,” Hall of Famer Spencer Haywood told The Undefeated. “Defensively, he was always stuck on your jersey. Guys were fighting and kicking at him just to get him off, and he’d stay right in there. He had that one-hand push shot, which was a beautiful thing to watch. He was so well coached coming out of Philadelphia.”

“He was a great player. He really was,” Jaleesa Hazzard said of her late husband.

But out of all of Walt Hazzard’s NBA challenges, the biggest had nothing to do with playing — it had to do with his name.

Walt Hazzard played under his birth name during his first four seasons with the Lakers and Sonics. He last played under Hazzard with the Sonics during the 1967-68 season, in which he made his lone All-Star appearance, scoring nine points in New York City’s famed Madison Square Garden.

His wife, formerly named Patricia Shepard, said they first began exploring Islam while spending time in her hometown of Washington, D.C., around 1970. Then-Milwaukee Bucks and ex-UCLA center Lew Alcindor, who changed his named to Kareem Abdul-Jabbar when he converted to Islam in 1971, introduced the couple to the faith.

“I was wondering why [Alcindor] was spending all this time in D.C.,” Jaleesa Hazzard said. “I didn’t know about the mosque. I didn’t know about the whole involvement in Islam in the very beginning. But, he and Walt always hung out because they were very close from the time Kareem came to UCLA.”

Walt Hazzard and his wife attended several dinner meetings to learn more about Islam at a home called the Hanafi Center in D.C. Abdul-Jabbar purchased the property for Islamic teacher Hamaas Abdul Khaalis, who split with the Nation of Islam in 1958 to found a rival Islamic organization called the Hanafi Movement. In 1972, Khaalis published an open letter attacking the leadership and beliefs of the Nation of Islam and its leader, Elijah Muhammad.

Jaleesa Hazzard was immediately skeptical about Khaalis.

“I just personally felt like it was way too controlling. Way too controlling. And, I felt that he might gut the values — that he wasn’t a very good person,” she said.

Walt Hazzard told his wife that he wanted to join the Hanafi Center as a family in 1970. Despite some reluctance, she joined her husband and they both were given the Muslim names Mahdi and Jaleesa Abdul-Rahman. The Abdul-Rahmans would go on to have four children: Yakub, Jalal, Rasheed and Khalil, a successful hip-hop record producer known as DJ Khalil.

“I remember the process. I remember having to shave my son Yakub’s head. That was traumatic,” Jaleesa Hazzard said. “This was Hamaas, this was his ritual. It’s a part of what they did, you had to shave your head. You had to take what is called a Shahada, where you say that you believe there is one God — it is Allah — and that Muhammad is his prophet. It’s a very simple process, but there was a lot of ritual around it.”

Mahdi Abdul-Rahman’s father, a Methodist preacher, had a very hard time adjusting to the overall change.

“That was a big deal. We were no longer Hazzards. So as you can imagine for my father in-law, and for his family, this is huge. He was like, ‘You’re a Hazzard, and now you’re not?’ ” Jaleesa Hazzard said.

Haywood said the changing to Muslim names by two standout NBA players, Abdul-Rahman and Abdul-Jabbar, was not warmly welcomed in America.

“When he changed his name, that was a big deal back then. It was wild,” Haywood said of Abdul-Rahman. “You had two players that changed their name to Islamic [ones]. Most people didn’t equate them as Muslims from a world perspective. They were looking at them as black Muslims with hate rhetoric, but they were about self-awareness black Muslims. It was confusing.”

On Jan. 18, 1973, Khaalis’ property was the site of a bloody terrorist attack known as the Hanafi Murders. Philadelphia-based Nation of Islam members invaded the home, killing two adults and five children ages 9 days to 10 years old. The adults and one child were shot to death while the other children were drowned. The victims were related to Khaalis.

The Hazzards fortunately were not at the house on that nightmarish, bloody day. Seven members of the Philadelphia-based Nation of Islam, who were connected to Elijah Muhammad, were later convicted and sentenced to prison.

“Hamaas had a beautiful, lovely wife, and he bought this big piece of property on 16th Street in D.C.,” Jaleesa Hazzard said. “There were very few black people at all in that neighborhood, and certainly no Muslims. And, he started this community with a lot of families living there, a lot of children. He had more than one wife, if I remember correctly.

“So, he was building his own community and in a certain way rivaling, and sort of considered himself a rival of the Nation [of Islam], which ended up becoming very dangerous. Eventually they came in and destroyed his community.”

The murders at the Hamaas compound didn’t dissuade Abdul-Rahman from following Islam. He actually grew closer and more knowledgeable about Islam after taking a trip to Pakistan.

“Walt first went to Pakistan right after he converted, and really got to see what Islam really was versus this version that they had through [the Hamaas] mosque when [he and Abdul-Jabbar] were first introduced to it. It changed his way of thinking about the religion, and he shared that with Kareem. And, that was something they grew into together,” Jaleesa Hazzard said.

Walt Hazzard was playing for the Hawks when he changed his name to Mahdi Abdul-Rahman in 1971. Jaleesa Hazzard recalls her husband’s teammates being very supportive and loving the knit kufi cap he wore daily. She said Hawks ownership and management had a harder time adjusting to the changes.

“They weren’t the most enlightened bunch in the beginning,” Jaleesa Hazzard said. “I’m sure they had serious conversations about it with him … I don’t think they had much of a choice.”

Walt Hazzard actually didn’t want his wife and family to live with him in Atlanta because of the racism, which included the playing of the Confederate song, Dixie, before Hawks games.

“I was still in Seattle. We had sold our house. He calls me, he says, ‘I don’t know if you really need to come down here right now, because they played the f—— Dixie at the first game.’ When the Hawks went to Atlanta, they did not play The Star-Spangled Banner, they played Dixie. I’m not playing with you.”

Abdul-Rahman played with the Buffalo Braves — now the Los Angeles Clippers — from 1971 to 1973. It was there that his wife and Haywood say they experienced the most resistance from the NBA, team management and the fans. Haywood described it as a “lack of understanding.”

“In Buffalo, it was an issue, and you could tell,” Jaleesa Hazzard said. “There were people who didn’t like him. You could tell that the league was concerned about it a little bit. ‘Is this some kind of a movement? What’s happening here? Are we hurting the brand because, again, this was an expansion city?’ You’re trying to grow your audience. You’re trying to make sure that he’s a star … ’

“I thought there were questions from [fans]. You could hear comments like, ‘Why did he change his name?’ You could hear people discussing it.”

“There was a lack of understanding. [Buffalo] is where he was really treated bad,” Haywood said.

After Abdul-Rahman rejoined Seattle during the 1973-74 season, Haywood said, he began following Islam when the two began studying the religion together. Haywood considered changing to a Muslim name before being scolded by his mother, who worked in the cotton fields of Mississippi. Although Seattle was more welcoming to Abdul-Rahman, Haywood recalled his challenging experiences with other black Americans.

“He told me about some of the stuff that he and Kareem were going through,” Haywood said. “I said, ‘This is just for trying to clear your soul and be better people?’ They were being treated totally different. Then you went through it with all of the brothers … You’d be playing and Walt was not Walt anymore. They were saying, ‘Mahdi’ or ‘Rahman.’ He would say, ‘My name is Mahdi Abdul-Rahman.’

“So when you say it long, brothers wouldn’t want to hear that. They would say, ‘I’m calling you Walt.’ He took it very seriously.”

Abdul-Rahman averaged 3.8 points and 2.5 assists in 11.7 minutes per game with the Sonics during the 1973-74 NBA season, which ended up being his last. He was invited to training camp with the Detroit Pistons in 1974 at the age of 32. While his wife doesn’t recall whether he quit the Pistons or was waived during training camp, she said that he called her and said he was retiring from playing basketball.

Years later, Rasheed Hazzard asked his father if he retired because of the ridicule he faced as a Muslim.

“I asked as I got older, like, ‘Well, if you didn’t change your name and convert to Islam, would you have played more in Buffalo? Would you have ended up playing in Detroit? Would you have went back to the Lakers? Would you have gone to New York? You were a ‘Showtime’ player,’ ” Rasheed Hazzard said. “And, he would just say, ‘I chose my path. I decided what I wanted to do. I have no regrets. I don’t look back. And, if those things happened, then those things happened … ’

“What he was doing in that moment was actually teaching me what the religion is about. It’s just being humble, kind.”

Abdul-Rahman’s family says he was very proud of his name and his religion and never changed it legally back to Hazzard after he retired from the NBA. However, he did ultimately decide it was best to go by Walt Hazzard publicly.

Abdul-Rahman was the name he used in his first coaching job with Compton College. But local media and fans often used the name Hazzard in describing him since that was what they were familiar with from his UCLA days. He went back to using his birth name publicly as a coach, starting with Chapman College.

Jaleesa Hazzard, who uses Abdul-Rahman privately, described the use of both names as a “dual life.”

“He realized the cache of it,” she said. “If he really wanted to coach, he decided that Hazzard is what people knew him as. He made his name in this town, and the name he made was Hazzard from playing at UCLA. So he decided to use that.

“It didn’t bother me. It was fine. But, around [home], he’s always Abdul-Rahman.”

Rasheed Hazzard used the Hazzard surname while working with the Lakers and the New York Knicks as an assistant coach, scout and in player development, but his emails and checks would say Abdul-Rahman. He said the name Abdul-Rahman caused him difficulties going through security at airports following the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. He also believes he was recently deemed unqualified for an assistant coaching job for one NBA Western Conference team after the head coach learned he had a Muslim name.

“[My father] didn’t want me to deal with any backlash or any misunderstanding or anybody, you know, trying to profile me, as a certain kind of person, based on my name and my religion,” Rasheed Hazzard said. “He was always very proud of being Abdul-Rahman, loved it. We used Abdul-Rahman. All of us changed our name.

“This wasn’t a lack of pride thing. This was a looking out for your son going into an industry you’ve already been in thing.”

Under the name Walt Hazzard at UCLA, the 1987 Pac 10 Conference Coach of the Year made one NCAA tournament and won the 1985 National Invitational Tournament. He had a 77-47 record at UCLA during four seasons, but was fired after the 1987-88 season. Hall of Famer Reggie Miller said he played at UCLA in large part because of the atmosphere that he provided.

“We were all always invited to come over and have food and watch games and just hang out,” Miller told The Undefeated. “I think that’s what made our UCLA family so special and tight is because of that open-door policy. That’s probably why I stayed all four years is because I really enjoyed my time at UCLA and the family-type atmosphere that surrounded that program.”

“Zero. Not one time. Nothing,” Miller said. “Of course you knew, but it never came up. He never brought it up. I never brought it up because we focused on academics, we focused on athletics, and that was it. We didn’t talk religion or politics or anything like that.

“If I wanted to, I’m sure he would’ve. We just never did.”

After his coaching days with UCLA, the Lakers hired Abdul-Rahman as an advance scout and he used the name Walt Hazzard.

On March 22, 1996, Abdul-Rahman was hospitalized after a stroke. He never fully recovered physically, ending his ability to be an advance scout for the Lakers. Then-Lakers owner Jerry Buss said Abdul-Rahman would remain a Lakers employee for the rest of his life with health insurance, four Lakers season tickets and two parking spots. The Abdul-Rahmans’ Los Angeles home still has a Lakers logo painted on the curb.

“My mom [was] concerned about health insurance and his paycheck,” Rasheed Hazzard said. “The day before he [went] into surgery, you look up and, not a messenger but [then-Lakers general manager] Jerry West walked off the elevator with a folder with a contract from Dr. Buss that basically said that he would have a job and get a check, and have season tickets until the day he wasn’t on this earth anymore. And he honored it, to the last day.”

After Abdul-Rahman’s surgery, he became a regular at the Lakers’ practice, where he developed a close bond with fellow Philadelphia native and Lakers star Kobe Bryant.

“I always tell people this one thing, Shaq [O’Neal] and Kobe, you can say they hated each other, they fought. But if there was one thing they agreed on, it was how much they loved my pops. You can ask both of them. They both took care of him,” Rasheed Hazzard said.

Abdul-Rahman would also attend Rasheed’s practices when he coached at Venice High School, and would later support his son when he worked for the Lakers. Before Lakers home games, they would often give each other a hand signal to acknowledge each other.

In 2011, Abdul-Rahman’s health began to worsen and he was hospitalized in intensive care. He died at UCLA’s Ronald Reagan Medical Center on Nov. 18, 2011, due to complications following heart surgery. During his final days, the one friend who spent the most time at his side was the man who introduced him to Islam.

“Kareem to the very end, like my dad’s last month, he was in the hospital for hours,” Rasheed Hazzard said. “Kareem was up in the corner of the room asleep or he was in there talking. You know people say Kareem doesn’t talk? He would talk. He would come sit in the room with him and my dad, and sit in the room with me.

“I guess he sees me like an extension of my dad. Me and Kareem have long conversations. And, he was one of the people when I was with the Lakers, to tell me the stories about my dad, and his connection to Islam, and why it was so important to my dad. He was like passing the stories along to me because [my father] couldn’t tell them himself.”

Rasheed Hazzard said Muslims often still come up to him to express appreciation for his dad. He hopes his dad’s story is an example to Americans of what a true Muslim is.

“I’ve met Muslims in New York, and my dad meant so much for them,” Rasheed Hazzard said. “Kareem, my dad, championed the cause for them. Not only were they proud Muslims, they also did it the right way. They were good men. They were family men. Say what you want about my dad or Kareem, but they’ve conducted themselves with dignity, and people respect them. And, if the media would put more attention on these Muslims, and these people doing these good things, there would be a whole different perception of what Islam is.”

Marc J. Spears is the senior NBA writer for The Undefeated. He used to be able to dunk on you, but he hasn’t been able to in years and his knees still hurt.