When 18-year-old Jim Stewart made the trek to Memphis from his family’s West Tennessee farm, he had dreams of becoming the next big country music star.

As it turned out, Stewart was instrumental in creating the world-famous Memphis brand of soul as a founder of Stax Records.

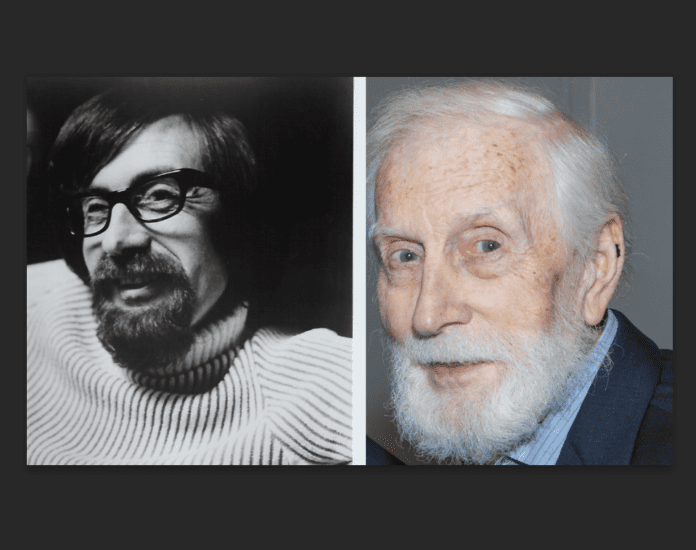

Stewart, 92, died Monday (Dec. 5), surrounded by his family, according to a statement released by Stax Museum Communications Director Tim Sampson.

For nearly 15 years, Stewart produced and recorded the songs of young, African-American bands and singers, creating a stable of stars from aspiring performers with a dream.

Hundreds of Stax singles topped the pop charts and dominated the R&B charts.

Stewart forgot all about his rockabilly stardom aspirations when he discovered the wealth of talent just waiting to be recorded. Those were the glory days of Stax soul.

“When I first heard that Mr. Stewart had passed away, I thought, ‘Wow, he was the man who gave us our first start,’” said James Alexander, an original member of the Bar-Kays. “His death marks the end of an era. Mr. Stewart’s death feels like the end.”

Stewart had rented a closed theatre at 926 at McLemore near College. He partnered with his sister Estelle Axton who mortgaged her house to finance the operation, named the venture STAX, (first two letters from each of their last names), and opened for business.

Memphis DJ Rufus Thomas and his daughter Carla Thomas, 16, recorded “Cause I Love You,” and Stax was on its way.

Alexander remembers when their band went down to Stax to audition.

“In those days, everybody had to audition live,” said Alexander. “We had been playing underage at the Hippodrome on Beale Street. We played behind this singer, Norman West, and there was a little groove we always played when we were there. So, we started playing for Mr. Stewart.

“He stopped us and said, ‘What is the name of that?’ And we said, ‘We don’t know. It’s just a groove we play at the club.’ So, he ran into the booth and started recording it. After a few little changes, we recorded that song and called it ‘Soul Finger.’”

Stax Records would launch other stellar careers, including Otis Redding, Isaac Hayes, Sam & Dave, Booker T. & the M.G.s, the Staple Singers, Johnnie Taylor, Albert King, among others.

Steward was lauded for his forward-thinking in the segregated South. Stax was praised for its integrated staff and roster of musicians. Stewart often would say he didn’t care about color. He just wanted to make music.

“It was magical,” said Alexander. “So many dreams came true. So many dreams of being stars—we were living the dream. And then, everything just suddenly stopped. There was the plane crash, and the Bar-Kays were gone.”

Dec. 10, 1967, Otis Redding and the Bar-Kays were on the way to do a show, but their plane crashed, leaving only one survivor, Ben Cauley.

“I wasn’t on the plane,” said Alexander. “We were all devastated. Mr. Stewart knew how close we were. We all transferred to Booker T. Washington (High School) so we could be together every day, including the white keyboard player, Ronnie Caldwell. He was at Central.

“Mr. Stewart came to me and asked if I wanted to continue the situation or just let everything go. I said I wanted to continue. And we just began to rebuild. I will always remember what Mr. Stewart meant to us and everything he did for us.”

Deanie Parker, Stax’s first publicist and later the first president/CEO of Soulsville, the nonprofit established to build and manage the Stax Museum of American Soul Music, Stax Music Academy and The Soulsville Charter School, recalled her association with Parker.

“When I first came to Stax, I came there to be a recording artist,” said Parker. “But after recording, I discovered that I just didn’t have what it took to be a recording artist. There were so many things in the segregated South that Black artists had to endure.”

Parker, who established the Soulsville Foundation and served as its President, said Stewart “helped me get into the administrative end of the business. I was a quasi- promotions person. I got all the demos out to the disc jockeys. I made sure all the promotional spots were prepared and distributed.

“And then, Mr. Stewart did something for me that anyone hardly does, unless you are in a family business,” she said.

“He opened the door and gave me an opportunity to get my formal education while I was getting on-the-job training. I went to Memphis State University for marketing. Mr. Stewart did that for me. I will always be so grateful.”