by Johnnie Turner and Steve Mulroy, Special to The New Tri-State Defender

In November 1974, the voters of Ann Arbor, Mich. approved the use of an innovative election method called Instant Runoff Voting (IRV).

Five months later, IRV allowed the election of the first-ever African-American mayor, Albert Wheeler, a 1960s civil rights pioneer and first black tenured University of Michigan professor who founded both the local NAACP branch and Ann Arbor Human Rights Commission.

Five months after that, local Republicans began a petition drive to repeal IRV, succeeding in an April 1976 referendum with very low voter turnout. Wheeler went on to lose the next election to a white Republican.

Such is the history of IRV, and any election reform that opens up the electoral process to the under-enfranchised. The establishment opposes the reform to defend the status quo.

Such is the history of IRV, and any election reform that opens up the electoral process to the under-enfranchised. The establishment opposes the reform to defend the status quo.

The City of Memphis is on course to try IRV for the first time in the 2019 City Council elections. IRV would enhance African-American voting power, and has a track record of electing minority and female candidates.

But the Memphis City Council is considering an effort to repeal IRV. This would be a shame.

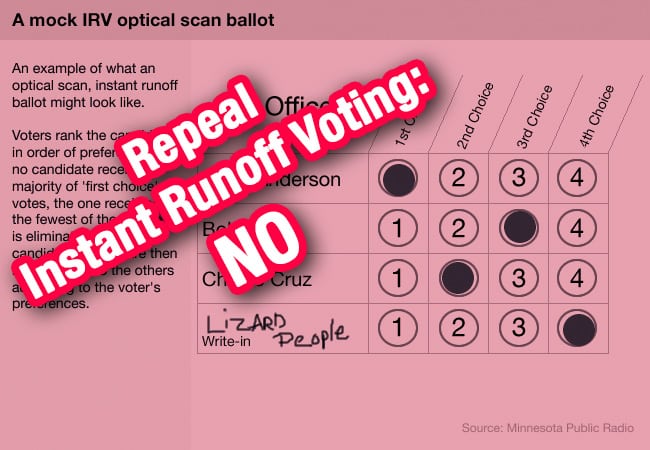

Under IRV, voters get to rank their candidates: First choice, second choice, third choice. If a candidate gets a majority of first-place votes, he or she wins. If no one gets a majority, the candidate with the fewest first-place votes is eliminated. Votes for that candidate are redistributed to the other candidates based on their second-place choice.

If there’s then a candidate with a majority, she is declared the winner. If not, the weakest candidate is again eliminated, and that eliminated candidate’s votes are redistributed as before. This process repeats until there’s a majority winner. (As a practical matter, you don’t go more than a few rounds before someone wins with a majority.)

IRV is used in 11 cities, including San Francisco, Minneapolis and Oakland. Nearby Arkansas and Mississippi use it for military and overseas voters in federal elections. The state Democratic parties of Texas, Iowa and Virginia use it for their primary elections.

Where it’s been used, it has consistently enhanced the election of women and people of color. That’s why it’s been endorsed by the Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr., and Congressman Jesse Jackson Jr. The Memphis NAACP endorsed it back in 2008, when Memphis voters approved it in a referendum by 71 percent.

And it’s not hard to see why.

The prior system made Memphis voters go to the polls once in October, and then come back again in November for the runoff. Turnout dropped dramatically in the runoff, going from 28 percent turnout in October to only 5 percent turnout in November. Crucially, that drop-off in turnout is highest among black voters. With runoffs, the final, decisive election takes place when black turnout is at its lowest.

Indeed, this disparate impact on black voters is true in any runoff. That’s why the Justice Department Civil Rights Division sued Memphis for voting discrimination in the late 1980s, and why the federal court barred the use of runoffs in the mayor’s race.

So it’s no surprise that the local NAACP supported IRV in 2008, and worked hard to get the referendum passed. Unfortunately, implementation was delayed for nine years through foot-dragging by the Republican-controlled local election commission, which claimed inaccurately that our county’s voting equipment couldn’t handle IRV. But a new election administrator has acknowledged that we can do it here in Shelby County, and plans to follow the law by implementing IRV in the 2019 City Council races.

And that’s what will happen, unless certain city councilmen get their way. They want to put on the ballot a referendum to repeal IRV.

They say it’s too confusing for Memphis voters, even though voters in other cities using IRV, including voters of color, overwhelmingly report that it’s easy to use.

They say voter education will cost too much, even though IRV has been certified to save Memphis money, because we won’t have to pay for that second election.

They complain that it may take four or more days to find out election results, without mentioning that under the current system, it takes six or more weeks to get final results, because you have to wait for the runoff. (At any rate, all first-round results would be posted on election night same as always, and in almost half the cases, that would be enough to determine the final winner.)

They say that fourth-place “losers” can somehow become winners under IRV, even though that has never happened once, and by definition anyone with few first-place votes would be eliminated quickly.

The City Council will be making this decision over the course of the next month. Please contact the City Council and ask them to give IRV a chance. Let’s try it at least once before we even begin to consider repealing it. Even 1970s Ann Arbor, Michigan did that much.

(Johnnie Turner represents District 85 in the Tennessee House of Representatives, and served as executive director of the Memphis NAACP during the 2008 IRV referendum.)

(Steven Mulroy is an election law professor at the University of Memphis and was a civil rights lawyer for the Bill Clinton Justice Department.)