by Edmund Ford Jr., Special to The New Tri-State Defender

Voting should be an easy, trusted process. Registered voters should be able to go to their precinct, provide proper ID, push the button for their choice of candidate for each race, and go home, knowing that their vote was tallied and counted.

That ease and trust in the process is now in jeopardy if instant runoff voting (IRV) is implemented in our City Council races. Although this measure was passed in a crowded field of referendum items almost eight years ago, several of the people I meet with in the community on a daily basis have no idea how IRV works and what the negative consequences are to them as voters and to the integrity of our process overall.

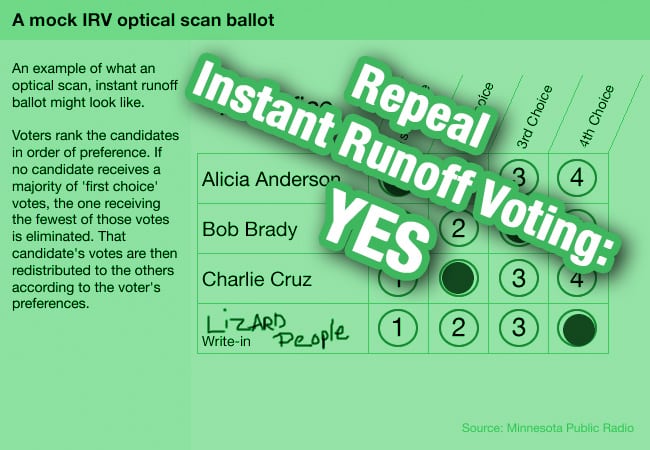

This new process makes the voter rank her/his top three candidates in contrast to picking one choice. If no one receives the majority outright, candidates are eliminated by receiving the lowest number of first-place votes. That candidate’s first-place votes are now redistributed to the voter’s second choice (or third choice if the second choice is already disqualified).

This new process makes the voter rank her/his top three candidates in contrast to picking one choice. If no one receives the majority outright, candidates are eliminated by receiving the lowest number of first-place votes. That candidate’s first-place votes are now redistributed to the voter’s second choice (or third choice if the second choice is already disqualified).

The process continues until someone wins. If the voter’s top three candidates are all disqualified, then the vote is considered “exhausted.” In other words, the computer throws your vote out as if you never voted in the first place. The reader probably dislikes knowing there’s a chance votes are thrown out under this new system. After all, we participate in the process because we want to “count!”

Those that try to convince you to embrace the change to IRV will do their best to inform you that this transition will do the following: save taxpayer money, improve voter turnout and trust, get results faster, and enhance minority voting strength. This Councilman is unconvinced and will dispel these untruths with real examples not sponsored by out-of-state interest groups who want to infiltrate in the way we vote for our elected officials.

Runoffs in Memphis cost the taxpayer $300,000 every four years. Those who support IRV state that the new system will only cost $60,000, but they intentionally leave out the costs for startup and continuous voter education, neither being one-time expenditures.

In Oakland, CA, approximately $3.51 per voter was spent to initiate IRV and to educate constituents, a $1.14 million overall spend. If we use Memphis’ 403,227 registered voters as an example from the 2015 election, Memphis would have spent approximately $1.41 million for voter education only.

Minneapolis, Minn. is still paying for ongoing education costs of IRV, up to $250,000 a year. “It is disturbing to me that we’re talking about an extra quarter of a million dollars for a system that was supposed to decrease out costs,” Minneapolis Council President Barb Johnson is quoted as saying.

Again, where is this cost-savings?

Those who like IRV do not go deep into the mathematics that happens either by computer or behind the scenes when votes are recounted, redistributed or thrown out. This would pose questions of trust in the system. On October 3, Election Commissioner Linda Phillips said there’s the possibility of someone ranked fourth winning the overall election. When should fourth place be our winner?

While Phillips used an arbitrary example, let me give you one with substance. In San Francisco’s November 2, 2010 Consolidated Statewide Direct Primary Election, 17,808 people voted. The third place candidate won the election with 4,321 votes, not even close to the majority of votes, which in this case would be 8,905 votes. If that isn’t shocking enough, 9,503 ballots were thrown out, which is more than half the electorate.

How can you trust a process where votes are recalculated, thrown out and third place wins? Is that true democracy?

Another untruth is that we receive results faster. I have mentioned that the Election Commission plans to recount the ballots by hand. That takes time, especially when you are talking about counting tens of thousands of votes with complete accuracy.

To give a real example, consider Pierce County, Wash. They repealed IRV after experimenting with it and ending up with adverse results. In their repeal ordinance, it was stated that the cost of running IRV proved “to be expensive, complicated, and confusing, and the results were not available for weeks following the election date.” I have to agree with my Council colleague, Phillip Spinosa, when he replied to the Election Commissioner about the wait time with the comment, “Are you serious?”

Finally, any supporter who wants to say this new system is responsible for electing minorities and women should stop. Believing this is like giving the rooster credit for the sunrise each morning.

In Charlottesville, Va., the local NAACP spoke out against the use of IRV and its complicated ballot format. Additionally, it was stated that the new system made voting “difficult for elderly voters, disabled and visually impaired voters, new voters, and voters with limited education.” One of those elderly voters, who has voted since the 1940’s, compared the new process to the “poll tax.” The last thing we need to do is to disenfranchise people who want to be part of the voting process. Again, voting should be easy to everyone.

There is no reason to tinker with our election system, and our elections should not be a professor’s experiment on our right to vote, a right that was given to us because of the sacrifices of others.

If you want to take the risk of using a system that has shown its significant flaws in other cities and has been repealed, then you should take the chance with IRV.

However, if you want the manner in which you vote to be simple and uncomplicated, I ask you to support my Council colleagues and me in voting YES to repeal instant runoff voting when it goes back to you, the voter. I want your vote to count.