The nearest Hal Pontez could get to the North Houston office park he owns was a quarter mile away. From that viewpoint on Monday, he said, “tops of buildings are peeking through a lake.”

One building houses another business he owns that builds electric power plants and services gas and steam turbines. It was having its best year ever, and its shop was packed to capacity with industrial control systems and sophisticated tools used in maintenance and repair.

Mr. Pontez has federal flood insurance. Experience has taught him it may not cover all his losses.

Business owners across the country say the National Flood Insurance Program, the only option for most since private insurers largely got out of the flood business nearly a century ago, is sorely out of step with their needs. Insurance experts and some government officials agree. The program’s limitations will be sharply tested when Harvey’s catastrophic floodwaters recede.

The federal program was primarily designed for homeowners and has had few updates since the 1970s. Standard protections for small businesses, including costs of business interruption and significant disaster preparation, aren’t covered, and maximum payouts for damages haven’t risen since 1994.

In last year’s April flood in Houston, Mr. Pontez’s damage exceeded the $500,000 insurance maximum on most of his affected buildings. The $500,000 maximum in coverage for equipment and other contents fell more than $200,000 short of losses at the turbine business. The policy didn’t cover any losses related to being closed.

The need for flood insurance that works for businesses is more dire because devastating storms are hitting the U.S. with increasing frequency.

Twenty storms causing a billion dollars or more in damage have taken place since 2010, not including Hurricane Harvey, compared with nine billion-dollar floods in the full decade of the 1980s, according to inflation-adjusted estimates from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Seven have hit just since 2016, including October’s Hurricane Matthew and February’s California flooding. A preliminary estimate on Tuesday by Moody’s Analytics is that Harvey will cause up to $75 billion in damages, with up to $25 billion of that in damages to businesses and lost economic output.

Less-severe flooding in monitored coastal towns has risen an average of 30% over the past five years and 150% over the past 20, said William Sweet, an expert on rising sea levels at NOAA.

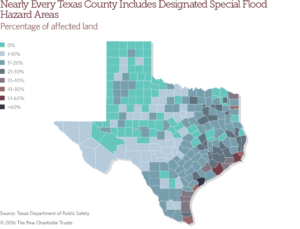

About 20% of NFIP claims between 2006 and 2015 came from outside areas considered high risk for flooding, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which manages the flood insurance program, told Congress this year. Businesses can have some losses offset by community funds and other programs.

A FEMA advisory committee said in a 2015 report that increased development in floodplains, sea level changes and changing climate patterns have resulted in greater flood damages.

When a freak storm dumped a torrent of rain on Ellicott City, Md., last summer, more than 5 feet of water swept through the Bean Hollow cafe, destroying a coffee roaster, brewers, grinders and espresso machines. Floodwaters burst through one wall, damaged joists under the building and gutted the electrical wiring and plumbing.

Owner Gretchen Shuey closed for more than eight months to rebuild, spending $250,000 and losing potential revenue of $450,000.

Her federal flood insurance payout was $109,000. She said she was barely able to reopen and had to depend on personal savings and donations from the community. She turned to Medicaid for her children’s health care.

Ms. Shuey’s private insurance for other calamities would have covered her lost business if fire or a tornado had hit her coffee bar and roaster in Ellicott City’s historic district. “If I had burned down, I would have had income for the last 8½ months,” she said.

Congress is supposed to reauthorize funding for the program’s next five years by Sept. 30. A Senate bill introduced this year would direct the flood program to study adding business-interruption coverage. A separate House bill would make flood insurance optional for businesses that are required to purchase coverage because of their location in federally designated flood zones. A temporary reauthorization of three to six months is possible, according to industry lobbyists, who say Harvey puts additional pressure on Congress to make sure the program doesn’t lapse.

FEMA is working with Congress to determine whether additional coverage should be added, said Roy Wright, deputy associate administrator for insurance and mitigation at the agency. Small businesses are a tiny part of the program, but “local economies would be able to recover more quickly” if more firms had coverage, he said.

In part because of the inadequate products on the market, nonresidential businesses account for just 1% of the NFIP’s 5.1 million policies; their $19.1 billion in insured flood losses are a small part of the program’s total $1.24 trillion in coverage.

Businesses are required to get flood insurance by some mortgage lenders when they are located in areas the federal government has determined to be high flood risk. The considerable cost and a misunderstanding of potential risks deter most small companies from buying flood coverage if it isn’t legally required.

Private insurers largely abandoned the flood insurance market following the Great Mississippi River Flood of 1927, one of the worst natural disasters in U.S. history. Flooding inundated 70 counties in seven states, according to government estimates. Damages totaled $1 billion, or about one-third of the federal budget at the time and the equivalent of about $14 billion in today’s dollars.

For comparison, NOAA estimates damage from 2005’s Hurricane Katrina, the costliest U.S. natural disaster, to be $160 billion in 2017 dollars.

Over the years, big businesses could acquire flood insurance through customized packages built to cover their commercial insurance needs, but homeowners and most mom-and-pop companies were left uncovered.

In 1968, Congress created the federal flood program in an effort to stem the rising cost of providing emergency aid through special disaster relief programs and to encourage sound land use. Flood policies were designed to provide basic coverage to help homeowners and businesses get back on their feet. Insurers say policies haven’t kept up with overall advances in the industry.

“The policy language hasn’t evolved much from the late 1970s and early 1980s,” said Don Griffin, a vice president with the Property Casualty Insurers Association of America, a trade group. He said that since the federal government program is “the only game in town,” there is little competitive pressure forcing it to improve the product.

Private insurers have been largely unwilling to write flood insurance because of the catastrophic nature of flooding, the difficulty of adequately predicting risk and the fear that only those at the greatest risk would buy coverage.

Before Hurricane Harvey hit, Mr. Pontez, the Houston business owner, called the flood program “antiquated and in desperate need of revision.”

Nearly 40% of holders of nonresidential policies opted for the maximum building coverage in 2016, according to FEMA, up from 20% in 2000.

“The trend is pretty dramatic,” said Erwann Michel-Kerjan of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development Board on Financial Management of Catastrophes. “We interpret that as essentially demand for more insurance.”

William Wilder purchased the maximum building and contents coverage for his Piggly Wiggly supermarket in Kinston, N.C. But when Hurricane Matthew caused the Neuse River to flood last year, sending 2½ feet of water through his store, losses totaled about $1.5 million. The maximum coverage is “just not enough,” he said.

Graig Cone, a developer in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, figures he lost about $58,000 in expected revenue from two restaurants during the six days flooding shut down the local business district last September. “I feel like there is definitely a gap that needs to be filled somehow,” said Mr. Cone, who has both federal flood insurance and standard business-interruption coverage that doesn’t apply in a flood.

Private insurers, who provide business-interruption coverage for other types of perils, use tools such as audits and data on local business conditions to better understand a firm’s cash flow, said Rade Musulin, a vice president for the American Academy of Actuaries. The federal flood program’s approach, by contrast, focuses more on understanding the physical characteristics of buildings and local flood conditions, and is less suited to measuring business losses, he said.

The Government Accountability Office said in a 2013 report that adding business-interruption coverage could “offset the need for some government disaster relief payments,” but could “further negatively impact the financial stability of the program” by increasing claims. Properly pricing risk, underwriting and paying out claims can be particularly challenging, the report added.

Lost sales and productivity, which are not covered by the federal program, and steps taken to protect properties from flooding, which are covered in a limited way, accounted for nearly 70% of the more than $6 million in losses reported by small and midsize firms in Cedar Rapids after the flood, according to a report released by the city in February.

Quinton McClain, co-owner of Lion Bridge Brewing Co. in Cedar Rapids, spent more than $13,000 to protect his restaurant and brewery from the flooding. His staff piled sandbags, boarded up windows and carted out furniture and kitchen equipment, and he hired plumbers to disconnect brewing equipment and plug drains.

“We were only able to claim up to $1,000 of those expenses for flood preparation,” said Mr. McClain. “It’s kind of crazy, but that’s the way it works.”

Small businesses also felt coverage gaps in the case of superstorm Sandy, which caused an estimated total of $70.2 billion in damage mostly along the Atlantic Coast in 2012, according to NOAA.

More than half of small businesses in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut that had flood insurance and suffered damages received no insurance payout, according to a 2016 study by the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Another 31% recouped only some of their losses, the study said.

Among those receiving no payout, 60% suffered a loss of customers, while 20% were hit by utility outages, according to an analysis conducted for The Wall Street Journal by the study’s lead author, Benjamin Collier. Overall, businesses were more than twice as likely to have suffered customer losses than physical damage.

“People were insured for different losses than what Sandy created,” said Mr. Collier, now an assistant professor at Temple University’s Fox School of Business.

Russell Rhodes, chief executive of Neuse Sport Shop in Kinston said his flood losses “were significantly higher” than the maximum covered by the federal government.

Mr. Rhodes had shopped for additional private flood insurance for his sporting goods store, but he said policies were “completely unaffordable.” He also looked at business-interruption coverage for flooding, but insurers only offered to pay claims if the store had been closed for 30 days. “I would have been paid nothing,” said Mr. Rhodes, whose store was closed for 20 days after the hurricane.

“The private sector is putting its toe in the water” in “a very nascent private market,” said Charles Symington Jr., senior vice president at the Independent Insurance Agents & Brokers of America, a Washington, D.C.-based trade group. Advances in flood mapping and analytics now make it possible to measure risk more accurately, he said.

But low prices of the federal program make it difficult for the private market to develop, he said. Rates are subsidized for some properties to encourage participation in the federal program. Congress began phasing out subsidies for businesses in 2016.

Private insurers also face higher costs for capital and must build large reserves to cover potential payouts, and, unlike the federal program, they face demands to make profits.

Until 2004, the federal flood program collected enough in premiums to cover most claims. It fell deeply into debt following Hurricane Katrina, when it paid out $16.3 billion. It added to losses after Hurricane Ike, in 2008, and superstorm Sandy, and currently owes the U.S. Treasury $24.6 billion.

The federal government hasn’t yet calculated the potential financial impact on the flood-insurance program of Harvey. The flood program has roughly 444,000 flood policies in potentially impacted counties in Texas and more than 490,000 in Louisiana, a FEMA spokeswoman said.

Those facing the greatest flood risk are more likely to take part in the government program, making it harder to balance risk and keep prices affordable by having a pool of customers who are less likely to make claims. The federal program doesn’t have the flexibility of a private insurer to reject customers who are too risky.

For Ms. Shuey, the coffee bar owner in Ellicott City, community support proved crucial to getting back on her feet. She said customers built cabinets for free and donated countertop granite, flooring, plumbing fixtures or cash. “A good 40% of our costs were probably covered by donations,” she said.

The outpouring helped persuade her to reopen at the same site on Main Street, a district that helps anchor the community.

“It was important to them and to us,” she said. Still, she added, “I can’t buy insurance to protect myself. It doesn’t exist.”

by Ruth Simon and Cameron McWhirter for the Wall Street Journal