The horrors of lynching and the act’s lasting effects on the psyches of the victim’s relatives and witnesses were laid bare during a day-long symposium at First Congregational Church.

“Confronting the Legacy of Lynching: A Conversation Among Descendants” was the fourth and final panel of the Memphis Lynching Sites Project’s awareness and learning gathering.

A broad multiracial crowd of attendees came to hear descendants of lynching victims and witnesses. The event was part of an ongoing effort to raise awareness of these inhumane racist murders and to have the site of the lynching of Ell Persons added to the National Parks Registry.

Steve Haley, whose great-uncle watched a rabid mob of white men soak Persons with gasoline and burned him alive, played a three-and-a-half-minute recording of his great-uncle’s account, while on his death bed, of the 1917 event.

“They poured gasoline on that n****r and burned him at the stake,” said the gravelly voice on the recording. “I can still smell the flesh of that n****r cooking…”

Haley, whose great-uncle was a white man, living in Memphis in 1917, remained silent after the recording ended. Finally, he spoke.

“Fifty years later, my great uncle could still recall the smell of burning flesh,” said Haley. “I am on this panel today, but I don’t really talk about it much. I get emotional.”

Persons’ lynching often is called “the worst lynching in Shelby County.”

Persons, an African-American woodcutter was accused of raping and decapitating a 15-year-old white schoolgirl, Antoinette Rappel, who was last seen on her bicycle crossing the Wolf River on the Macon Road Bridge.

The only “proof” that Persons was actually guilty was the coerced “confession” to the girl’s murder.

Haley remembers his great uncle’s account of May 22, 1917, when Persons was snatched from the custody of two officers bringing him back to Memphis on a train to stand trial. They dragged Persons off the train, beat and tormented him to coerce a confession to murder, and then proceed to render mob justice.

Haley recalls his ancestor saying it was clear that anyone who tried to interfere in the lynching would be killed.

Persons’ great niece, Michele Whitney did not find out about the lynching until 2017, well into middle age.

“Growing up, no one talked about it,” said Whitney. “This was not a part of our family’s oral history.

“I was contacted by Tom Carlson, a professor at the University of Memphis, who told me he believed that I was a descendant of Ell Persons. But I never heard anything about this growing up.”

Whitney acknowledged it has taken professional therapy to deal with wounds of the past and the painful secret elders in her childhood took to the grave.

“My father was four when our family moved from Memphis up to Chicago,” said Whitney. “History is uncomfortable. We must take a look at it, addressing the wounds. The only way out is through it.”

Laura Wilfong Miller, a descendant of the Antoinette Rappel family, also learned about her lineage from Carlson, who told her he believed she was Antoinette’s descendant.

“There has never been any indication that the real killer was ever found, or if Persons actually did it,” said Miller.

“I have a 14-year-old daughter, and I did share our family’s story and the lynching that followed Antoinette’s murder. Some discussions are difficult to have, but we must all keep talking to each other.”

Whitney and Haley extended each other grace, as they made peace with the past and each other.

“I continue telling my stories,” said Whitney. “Young people need to know. They need to connect to their history. I tell them we should never take our freedom for granted.

“Generations before us wanted us to do better and go further. We have an imperfect past, but a hopeful future.”

Haley, who taught history 40 years at Shelby State, (now Southwest Tennessee Community College), said lynching is a part of American history, particularly Southern history.

“I have always had discussions with my students that no one else was having,” said Haley.

“We talked about lynching, and surprisingly enough, those who objected to talking about it were Black students. They would say, ‘Why are you bringing that up.’ I understand. The past is painful.”

Haley, too, sees honest and sometimes, painful conversation as the way forward.

“After World War II, things had gotten somewhat better,” said Haley. “My daddy used to say that everybody has a soul, Black or white, and that everybody had a right to be saved.

“There is some change. Some other things are racism in a different package. Together, we can heal each other.”

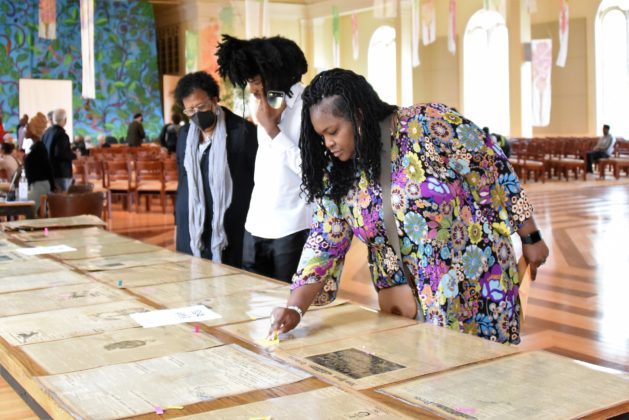

GALLERY