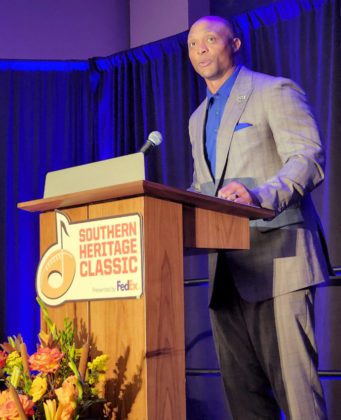

In what he acknowledged as “a great environment of Black excellence,” Penny Hardaway delivered a keynote message threaded with his God-embracing belief that getting involved in young people’s lives at the deepest level possible is a reward in and of itself.

It was, he said, his first keynote address. The venue was the Southern Heritage Classic Coaches Luncheon at the Renasant Center in Downtown Memphis on Friday (Sept. 9). The giants in the house notably included Tennessee State University football coach Eddie George and Jackson State University’s Deion Sanders.

“At the end of the day, we can’t forget about our youth,” said Hardaway, a Memphis favorite son and head coach of the University of Memphis men’s basketball program. “I love my city, that’s why I came back. I’m in the neighborhoods, I’m in the city. I came back for that reason because they need us. …”

In a passing, contextual reference to the “young man” whose recent killing spree stunned Greater Memphis, Hardaway said, ‘I’m partnering with people in this city to try to help understand and get these kids into whatever we need to do to try to grab our cities back.

“We (his generation and others before) had the pastors, we had the neighbors that could give us a whipping and then take us to our mom or grandma and we’d get another one. We don’t have that no more. We need that. We need the men to step up.”

Honored to keynote the Classic’s Coaches Luncheon, Hardaway, who starred at Treadwell High School and Memphis State University (now the University of Memphis) before becoming a household name in the NBA, said SHC founder Fred Jones Jr. essentially told him to “Do you.”

To Hardaway, that boiled down to sharing “the blessings that have happened in my life.” So, he respectfully asked the audience if he could share his story. Receiving a collective, go-for-it response, Hardaway engagingly wove a narrative that underscored his message.

Some parts were familiar to many who have followed Hardaway’s journey from Binghamton to stardom. On this day, however, the totality of his story and the timeline he shared stirred many to leave the banquet hall with an enhanced sense of inspiration.

“My momma had me when she was 19 years old, senior in high school. I’m saying this to show you where I come from to where I am right now. … So, my dad was gone before I was born. At five years old, I was dropped off at my grandmother’s house and my mom took off on her journey (pursuing a singing career). She stayed gone nine years. …

“When I moved in with my grandmother, two things I knew right away about my grandmother. She loved God and she was all about respect. And that got instilled in me very early.”

His grandmother was 55 and about ready to retire when she took in her five-year-old grandson.

“She was by herself, so she had to be tough. She raised me tough. She was … a woman that would sit on the front porch in the summertime, have a blanket over her lap and have a gun next to her. That’s the way I was raised, so y’all know I’m from Memphis.”

Much of his nearly 30-minute address was told that way: simple, direct and heartfelt with the intentional sharing of learned lessons. As a whole, it reflected that things often don’t unfold as one had dreamed, hoped and desired.

Hardaway desired to have spent more time playing with Shaquille O’Neal in Orlando, where he still believes they would have won multiple championships. He hadn’t wanted his NBA career to end when it did, but injuries and team circumstances dictated otherwise.

Baffled in an unwanted retirement, Hardaway returned to Memphis to be with a friend, Desmond Merriweather, who coached basketball at Lester Middle School and had been given 48 hours to live in a battle against colon cancer.

“When I started talking to him, it was nothing about his condition. He talked about these kids in our neighborhood, that he was trying to give pride back to them about being from where they were from and he was trying to get some help from somebody that he knew had the same heart as him.

“He knew I had the resources and the funds to give them an avenue to try to make it out … because we made it out. …”

After a visit by “a bunch of prayer warriors from our neighborhood,” Merriweather moved from ICU to a regular room to his own home.

“Come on now. Thank you, God,” said Hardaway, recounting the call he got soon after.

“You know what we have to do,” he heard Merriweather say. “We got to get to them kids in our neighborhood. And most of the kids that were on that team were from people that we grew up with in the neighborhood.”

Hardaway started going to practices. As Merriweather, who was receiving chemotherapy, weakened, Hardaway took on the head coaching duties.

“He didn’t miss one game while he was going through chemo. You couldn’t make him stay at home, because he was like, ‘I have a bigger purpose in me for what we’re doing. We’re trying to get these kids out of here. We don’t want them to be stuck.”

The middle-school team won the state title on a buzzer-beater.

“I looked at the bench and ran to him and he couldn’t get up he was crying so hard. And then I started crying because I knew what that meant. It wasn’t about his cancer. He was like, ‘Man, we did it for them. We did it for them.’”

From that point, said Hardaway, “I knew what the mission was. We have got to get these kids from trying to think about the streets and think about being on Wall Street.”

More titles followed. Merriweather followed the players onto the high school level as head coach at East. Hardaway decided to take the break he had put on hold after retirement. Several months later as he was leaving church, he got an unnerving call.

“So I race over. … We knew it was close because Desmond himself started saying, ‘I’m ready. … I’m ready now. The pain is so unbearable. … I feel like we’ve done what we needed to do. I’m ready.’ …

“(H)e’s gasping for air. I’m witnessing this, and he says to me, ‘I love you, dog.’”

Hardaway paused in the telling of his story to compose himself.

“It’s all right. Take your time,” several called out from the audience.

Gathering himself, Hardaway fast-forwarded, detailing how he subsequently took over the East coaching duties, the state titles that followed and his ascension to head basketball coach at the University of Memphis, where, he said, “I’m getting into trouble for doing what I just told y’all I do.”

The trouble, of course, is the pending NCAA probe, which, in part, involves Hardaway having paid the moving expenses from Nashville to Memphis for the family of an AAU team member, who helped Hardaway and East High School make state title runs.

“We got a group of people, who are judging me as if I did that for monetary purposes,” said Hardaway, “not from the heart. I did all that from the heart.”

He recalled a sermon in which his pastor at the time “put like 10,000 sheets, it was a bunch of sheets of copy paper on the stage one Sunday. And he said this is my life story in all these sheets of paper, but y’all want to grab one sheet and judge me from (one) sheet instead of understanding what the story is.”

Whether the NCAA will get the full story and whether that will affect the outcome is pending. Thanks to the Classic and its founder, Hardaway has had the chance to tell it from his vantage point and to do so as part of honoring two gridiron legends – George and Sanders.

“I love those brothers, man. It means a lot to me, as another Black man to see y’all take steps, strong and professional … To be having these kids dream through you guys, to be a father, to be a counselor, to be a friend, to be whatever. … You got to really invest in these kids.

“So, I’m here now, and I’m doing the same thing, and all this noise is going on. But the reason why I told that story is because nobody believed that any of that could happen. And, I’m on my knees saying, ‘Look what God did. God did it.’”

Concluding, Hardaway said, “We all need to step up.”

“That’s right,” came the chorus-like response.

“And that’s why I commend these guys (George and Sanders),” he said. “At the end of the day, I look at it like this, it’s not how they see us, it’s how we see us. … Thank you for listening to my story. I love y’all.”