Memphis has a long and complex history with race, power and civil rights. From pre-Civil War days to 2018, there’s been hatred, slaughter and systematic oppression, but there’s also been a strong thread of resistance, resilience, and collective Black power woven through the years.

It’s a movement that helped save the lives of enslaved people on the Underground Railroad, helped Black voters sway white politicians during Jim Crow, and put Memphis squarely in the spotlight of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. It’s a thread that continues today, as our majority-Black city faces high poverty, low educational attainment, and poor health indicators juxtaposed with major revitalization efforts from the grassroots to government levels.

Jacob Burkle and The Underground Railroad

Today, a modest farmhouse stands at the northern edge of Uptown as an example of the early days of the fight for Black liberation.

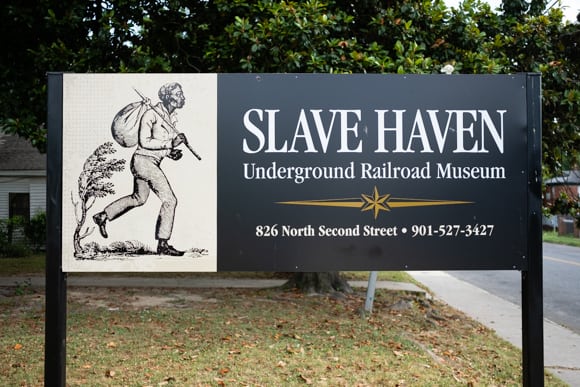

Located at 826 North Second Street, the white clapboard house was erected in 1856 by Jacob Burkle, a German immigrant and owner of Memphis’ livestock yards. Today the Burkle home is the site of the Slave Haven Underground Railroad Museum. The museum is an independent nonprofit founded by the home’s last resident, Helene Phillips, who bought the home in 1985. It first opened to the public in 1991 and is managed by Elaine Turner and her company, Heritage Tours.

According to the museum’s extensive research, Burkle was an abolitionist sympathizer and member of the historic Underground Railroad.

Slave Haven, a museum at the Burkle Estate, in Uptown Memphis. (Brandon Dahlberg)

Slave Haven, a museum at the Burkle Estate, in Uptown Memphis. (Brandon Dahlberg)

In the late 1840s, Burkle fled Germany and conscription into the army to avoid fighting in a series of revolutionary wars he saw as unjust and oppressive. He landed in Memphis to find himself surrounded by an entirely new and heinous form of oppression, chattel slavery.

Within a few years, Burkle built his stockyard business and his home on what was then the rural outskirts of the Memphis township. Memphis’ first subdivision, today’s Uptown but then called the Greenlaw Addition, was just being built to the southeast of Burkle’s estate and the Pinch District was still a tiny patch of small businesses and ramshackle dwellings to the south.

Related: “Uptown & The Pinch: How Memphis’ oldest subdivision became its newest boom town“

The museum’s research shows he hid slaves in the house’s cellar, crawl space and likely the attic until the end of the Civil War and full emancipation in 1865.

His home on the northern edge of the city, bordered by swampy areas perfect for wading out to a waiting boat, would have been the ideal location for the city’s last stop before heading upriver towards Canada.

There is some debate as to whether the Burkle estate was part of the Underground Railroad. The few primary documents supporting the claim were destroying by Burkle’s great-granddaughter. What remains are oral histories and the house itself, which has several odd and unique features (like a trap door and hidden staircase) that the museum points to as evidence of its true purpose.

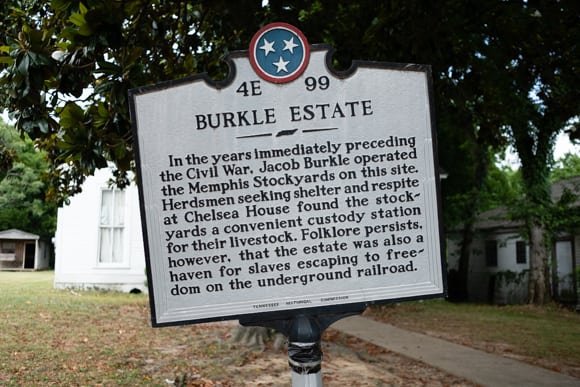

In 1991, research was conducted by an Atlanta-based Otis Johnson, who owned land located adjacent to the Burkle home that was once part of the estate. Johnson found enough evidence that the Tennessee Historical Commission placed a plaque in 1991 to commemorate the stockyards and noting the oral traditions as ‘folklore.’

A Tennessee Historical Commission marker acknowledges the Burkle estate. (Brandon Dahlberg)

A Tennessee Historical Commission marker acknowledges the Burkle estate. (Brandon Dahlberg)

Both Turner and Wayne Dowdy, a historian and manager of the local archives at the Memphis Public Libraries’ Memphis and Shelby County Room, note that it’s logical there would be little physical evidence. Keeping records would have been incredibly dangerous for Burkle, his family, and the escapees, even after the war.

“They still could have burned his house down or killed him. You had old Confederates around here who’d just lost the war,” said Turner.

Regardless of the exact evidence, it’s a story worth telling and Slave Haven helps facilitate that conversation for thousands of visitors each year, including field trips for local school children and international tourists. The museum tells the history of slavery in Memphis and the Mid-South, detailing the atrocities from capture to enslavement and sometimes escape. It highlights prominent members of Memphis’ slaving industry, including wealthy trader Wade Bolton for whom Bolton High School is named, as well as leaders of the resistance movement, including Harriet Tubman and Burkle.

“This is a piece of history that should not be overlooked,” said Turner. “It’s the story of courage and bravery of a person like Jacob Burkle who risked his life to save others, as well as the brave Africans who ventured out seeking freedom.”

“They’re doing a public service by bringing it up and us talking about it, examining it,” agrees Dowdy.

Abolitionists and Early Resistance

Jacob Burkle built his estate in the 1850s when the battle between oppression and resistance had been raging for decades.

The first Africans were brought to the U.S. in 1619 by Dutch slavers. Black resistance to slavery is as old as slavery itself with well-documented histories of slave ship and plantation rebellions, subtle means of undermining overseers and production quotas, and, of course, escape via the Underground Railroad.

“It is plausible that an Underground Railroad cell would be operating in a place like Memphis,” said Dowdy.

All manner of people and goods came through Memphis, which was the only place in the region to work, trade, stock up on supplies and cross the river. And until the mid-1830s, abolitionist sentiments ran high here compared to most Southern cities.

According to Dowdy, the city’s first two mayors, Marcus Winchester and Isaac Rawlings, supported education for people of color and felt that slavery was economically necessary but morally reprehensible. They both supported solutions to end the institution.

Related: “Germantown’s secret history as a utopian colony for freed slaves“

In 1834, the state of Tennessee convened a constitutional convention. Memphis’ delegate called for the state constitution to abolish slavery. Unfortunately, the convention voted instead to strip the right to vote from freedmen, a right previously granted by the 1796 state constitution.

A wooden cutout of an escaping slave leans against the front porch of Slave Haven museum. (Brandon Dahlberg)

A wooden cutout of an escaping slave leans against the front porch of Slave Haven museum. (Brandon Dahlberg)

By the time Burkle built his estate 22 years later, sentiments had shifted in Memphis and abolitionists were pushed underground. In fact, a law that required all persons of African descent to carry a permit to walk or drive a carriage on city streets. It also banned them from holding meetings, include church sessions, without a white person leading.

“To me that’s a clear indication that Memphis’ position on slaves and African-Americans in general has hardened,” said Dowdy.

But the resistance was already established and it remained active in secret. Turner’s research has uncovered reports of abolitionist protests at the slave market and a house that was stockpiling supplies and hiding runaways. There’s also a rumor that the Hunt Phelan home was a stop on the Underground Railroad, largely due to an escape tunnel running under the home.

“Here, this was a safe house. This was a beacon of light here in spite of what was happening in the larger part of the city,” Turner said of Slave Haven and other homes like it.

In June of 1865, the practice of chattel slavery was formally abolished across the United States. Burkle went back to a quiet life of selling livestock and anti-Black sentiments remained a steady fixture in the city.

But in 1866, The Memphis Massacre took place. White men burned over 100 homes, churches, and businesses and killed almost 50 African Americans during a time when they faced job competition from newly freed slaved and occupation of Memphis by Black Union troops.

It remains among the worst racially motivated riot in U.S. history.

The Birth of a Black Political Powerhouse

While the riots were horrifying, they helped inspire another shift in Memphis’ political leanings.

“I think there was a reaction to that. Certainly from the African-American community to rally and organize more,” said Dowdy. Many white people were also appalled at the violence and began to soften their attitudes towards their Black neighbors.

Portrait of Robert Church Jr., an important political figure in the Black community during the 1910s and 20s. (Memphis Public Libraries)

Portrait of Robert Church Jr., an important political figure in the Black community during the 1910s and 20s. (Memphis Public Libraries)

In 1868 the state restored the right to vote for Black men. Just four years later, in 1872, the first African-American was elected to political position in Memphis. Alexander Dickinson ran with no opposition for a city council seat. The following year several Black men were elected as aldermen. Even the most conservative of white politicians understood that the tides were changing, and said as much in editorials from the day.

“They don’t really say it was a good thing, but they say this is an understandable thing and we accept it,” said Dowdy.

Evidence suggests that the 1870s and 80s were something of a golden era for cooperation between Black and white political leaders in Memphis.

Related: “Larger than the Lorraine: Local black history museums you haven’t heard of”

Around 1876, Edward Shaw was elected as the city’s Wharf Master, a position that would have required white votes to win. In 1878, during the worst of the Yellow Fever epidemics, a St. Louis newspaper ran an editorial accusing Black Memphians of grave robbing and other criminal activity. One of Memphis’ most conservative papers wrote a scathing response that highlighted the courageous work of the Black public, police, and militia members who were helping keep a dying city afloat. There was even a roughly 15-year coalition of Black political figures working together with former confederates against the common enemy of Northern political influence.

“It’s no utopia, but it lays the foundation for what we see in the 20th century of African-Americans voting in large numbers, the acceptance of that, [white cooperation] with Black organizations, and African-Americans carving out for themselves some power and influence,” said Dowdy.

But first, the 1890s saw another regressive swing of the political pendulum.

“You have this new generation coming along that is far more interested in venerating the old Confederacy than making progress so segregation begins to be implemented. But in Memphis, the African-American influence remains, however, there is a new line that African American candidates are unacceptable,” said Dowdy.

In 1892 the last Black man to occupy any elected position for the City of Memphis finished his term. There wouldn’t be another for 72 years.

Despite holding no formal political power, Black citizens still held considerable sway. White politicians knew they had to court Black votes and stay true to their campaign promises if they wanted to be reelected.

“Black voters were very sophisticated and intelligent in how they used their votes and how they organized,” said Dowdy.

One of the best examples of Black resistance and organizing powering in the early 20th is Robert Church, Jr. Church’s father was a prominent businessman who was actually shot during the Memphis Massacre and survived.

Alana Turner of Slave Haven demonstrates a portion of the museum’s tour. (Brandon Dahlberg)

Alana Turner of Slave Haven demonstrates a portion of the museum’s tour. (Brandon Dahlberg)

Church Jr. founded the Lincoln League in Memphis in 1916 which helped encourage Black residents to participate in the political process. They organized registration drives and even paid poll taxes designed to keep African-Americans from voting. Church Jr. was a delegate to several political conventions, courted for appointments by two U.S. presidents, and commanded the respect of Memphis’ most notorious political figure, E. H. Crump.

In 1964, Civil rights attorney A. W. Willis shattered the unofficial moratorium on Black elected officials in Memphis when he was elected to the Tennessee General Assembly. The following term his law partner, Russell Sugarmon, was also elected to the assembly.

These men ushered in a new era of formalized Black political power and helped set the tone for Black representation in Memphis.

Today A. W. Willis Avenue runs the southern border of Uptown just a few blocks from the Slave Haven museum and the roots of resistance that stretch back over 100 years. Their close proximity is a poignant reminder of the very long road the city has traveled towards Black liberation and racial equity.

But Turner thinks Burkle, Willis, Sugarmon, and their ilk should also be a reminder of future possibility, not just past events.

“It shows that an individual can make a difference,” said Turner. “You see something negative about the city, you do something positive, and it makes a difference in hundreds of lives. That’s what Jacob Burkle did.”

Beyond just one individual, Slave Have is also the story of collective power. The power of secret plans and locations shared between a network of people who worked together to undermine an inhuman institution, and it’s only the first chapter in Memphis’ fascinating and unique story of civil rights, collective resistance, and Black political power.

In an upcoming edition we will explore the years of the Civil Rights Movement and the modern day resistance through the stories of prominent families of Uptown, including Willis and Sugarmon. Follow us on social media for the culmination of Uptown and Memphis’ story of race, power, and politics.

A special thanks to Elaine Turner and Wayne Dowdy for their historical research and the archives of the Memphis Public Libraries’ Memphis and Shelby County Room for the many articles and documents that informed this piece.