Sick and tired of enduring 18 years of racially discriminatory working conditions and practices, Memphis’ African-American firefighters had enough.

Tired of being sick and tired (to borrow a phrase from the late civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer), those African-American firefighters formed the Pioneers Black Firefighters Inc. in 1973.

Their goal was to coalesce into a mutual support organization that also would fight the systemic racism faced daily from the time the city hired its first African-American firefighters – the 12 pioneers – in 1955.

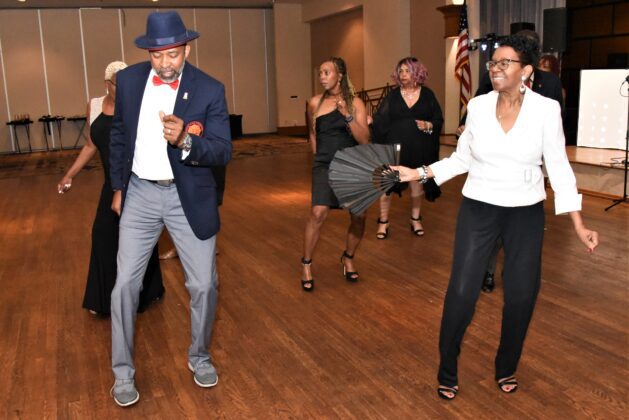

Last Saturday (June 3) evening, the Pioneers Black Firefighters celebrated the organization’s 50th anniversary during a gala at the Holiday Inn-University of Memphis.

TaJuan Stout-Mitchell, a former Memphis City Councilmember, and a former member of the legacy Memphis City Schools board, captured the celebratory theme: “As a wife of a firefighter for 37 years, I am proud to be in this firefighter’s family called the Pioneers.

“Thank you for your tireless work. Because of you, and citizens of this city, it supported our family of six. Educated and provided quality healthcare for our four children, who all are public servants,” she said.

“We lived a life of the middle class, which should be a reality for all city employees. Many of you can say the same. I am so grateful for men, who were treated like boys, but had the tenacity to fight a system of racism. Firefighters are truly fueled by fire and driven by courage…”

Stout-Mitchell’s son, Pioneer Black Firefighters President Ron Mitchell Jr., whose father Ron Mitchell served as president from 1987-2005, said the Pioneers were organized in 1973 because the firefighters’ union would not represent Black firefighters.

“Still in the ’70s, promotions, hiring and station assignments were not being done fairly; not until we started filing lawsuits and winning,” he said. “We made white leadership respect us.”

The 12 pioneers lauded for their steadfastness in breaking the color barrier at the Memphis Fire Department were: John Cooper, Murry Pegues, Robert J. Crawford, Else Parsons, Lawrence Yates, Earl Westley Stotts, Norvel Wallace, Leroy Johnson Jr., William C. Carter, Richard H. Burns, Floyd Newsum and Claude Talford.

After the event, a reflective Mitchell Jr. said, “Those guys took a lot so that those of us coming after them would not have to. When you just consider how the majority of Black people in their lives and with their employment opportunities had to take so much, we appreciate those first 12, who were hired and worked under deplorable conditions.”

Stout-Mitchell described some of the abuse.

“I have heard many stories from some of the original 12. I once heard the Black firefighters were not allowed to go the front door of a white homeowner, even though the house was on fire.”

Stout-Mitchell continued, “All the Blacks were assigned the same bed in the house, one Black each shift. I heard the guys would put their chairs in a circle around the TV to leave the Black outside the circle.

“I heard one Black firefighter was not allowed to eat the food at the station. All these racial personal indignities were day by day, but they (kept) focused on recruitment, hiring, advancement and promotion to change all of that for everybody.”

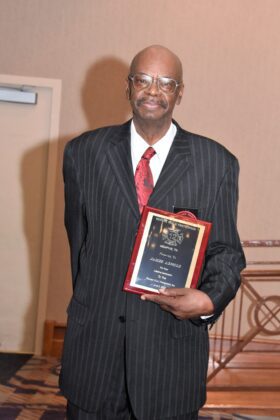

Chester Anderson, an early Black member of the Fire Department, was unable to receive his award in person, He reflected on his MFD career during a telephone interview the next day.

“I remember those early days quite well,” said Anderson. “That original class of 12 came in and worked out of the firehouse on Mississippi Blvd., Station 8. I came in 1972, and there were 13 of us in that class.

“They spread us out. The n-word was our name. I was at the airport station, and I got fed up. I threatened to file a complaint. Just the threat stopped all that.”

According to Anderson, many of the original 12 were fighting fires without an air pack – a portable oxygen tank that allows a firefighter to breathe in toxic smoke conditions.

“The union did not care that Black firefighters were placed in very hazardous conditions. We have really come a long way,” Anderson said.

On Jan. 1, 2000, Anderson became the first African-American to serve as fire department director.

“That happened because Dr. Willie Herenton was mayor,” said Anderson. “I remember getting a visit from the union president and vice-president up in my office when I was named Director.

“They were telling me what I could do and how things should go. They never cared about representing Black firefighters. I let them know in no uncertain terms that they would not be telling me how to run my office.”

The African-American firefighters took a momentous step toward fair treatment when one of the “pioneers,” Carl Stotts, filed a federal class-action racial discrimination lawsuit that resulted in a 1980 consent decree. It required the Fire Department to promote African-American firefighters in greater numbers.

Stotts had the full backing of the Pioneers Black Firefighters. The consent decree, along with a consent decree resulting from a class-action lawsuit filed by the Afro American Police Association, helped increase the number of African-American firefighters and police officers and the number of women in those positions. And, it spelled out a clear path for promotions.

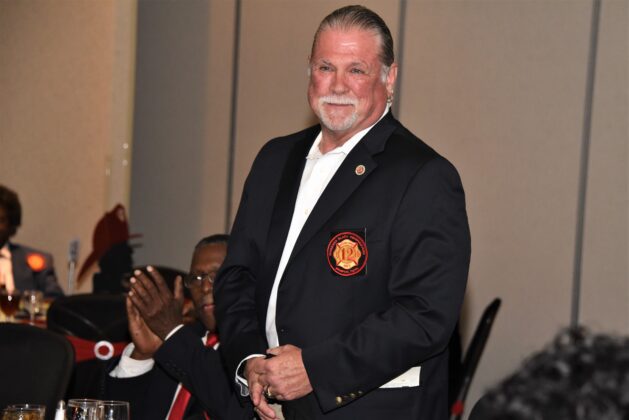

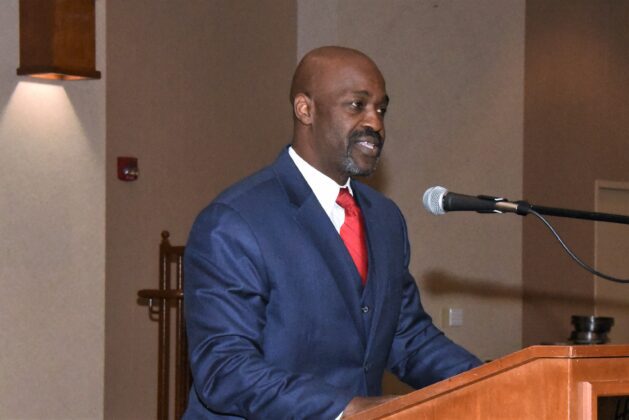

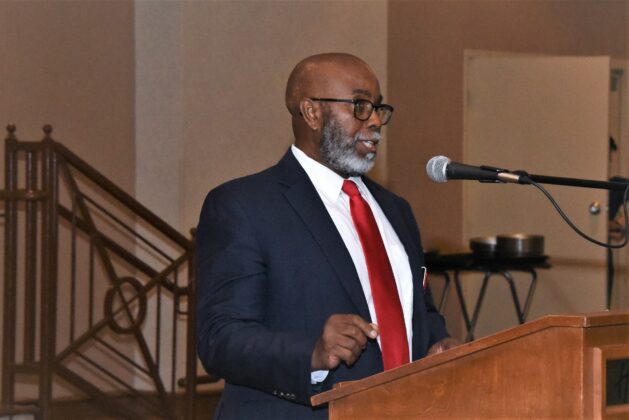

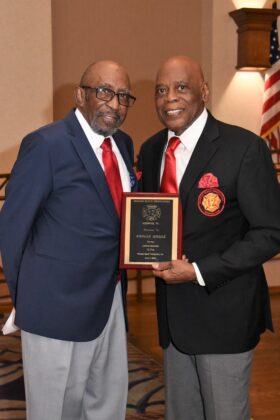

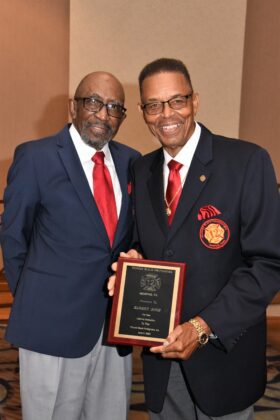

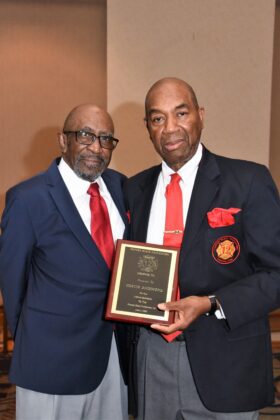

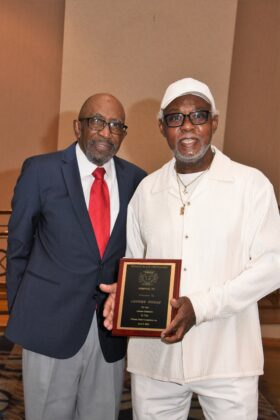

GALLERY:

Photos: Gary S. Whitlow/GSW Enterprises/The New Tri-State Defender

Mitchell Jr. talked about the relevancy of the Pioneers Black Firefighters today.

“In a time when conservatives are trying to erase the civil rights gains of the past, the Pioneers organization is as necessary as it ever was,” said Mitchell Jr. “Today, we have a white director (who is a woman) and only one African American in a high-ranking position.

“We feel that fire leadership should reflect the population of Memphis. So, we’d like to see more Blacks in top positions.”

Anderson struck an optimistic tone for the future of African-American firefighters.

“All in all, I had a tremendous career with Memphis Fire Department. May the young Pioneers make more strides in the next 50 years.”