Louise Polk Saulsberry, 91, just wanted a better life not only for children, but “for all of God’s people.”

As a result, she became an unlikely fighter against racial discrimination and unequal justice.

She waged a bold and courageous trek across Byhalia and Marshall County, urging African-American residents to register for the vote.

Byhalia, a town of some 1,300 residents, is on U.S. 78 about 30 miles southeast of Memphis.

Even at the age of 13, Louise Polk was what people back in those days called “a great beauty. Connie B. Saulsberry, 21, saw her for the first time and immediately set out to make her his bride.

Saulsberry was the son of Tommie and Effie Young Saulsberry, the hard-working and industrious parents of 12 children.

The two were married and became the parents of seven children.

Louise worked hard in the cotton fields. Connie was a farmer like his father. He opened Byhalia Fish Market in 1978, becoming a successful business owner for more than two decades.

The still-distinguished Louise recalls her past exploits with impressive clarity, while her children and grandchildren chime in with colorful detail.

Family lore has kept the stories of their ancestors and the family matriarch alive.

“I made it all the way to the ninth grade, and I could pick and chop 400 pounds of cotton a day,” Louise said.

As their seven children grew, “the Saulsberrys” wanted something better for their children.

Louise began working in 1973, when Byhalia’s population was about 700 people and Marshall County’s was about 25,000, with the NAACP in a door-to-door voter registration drive.

Louise and her one of her closest friends, Annie Lou Saulsberry, were spiritual mothers of St. Paul Baptist Church, one of the first Black Churches in Byhalia. They preached, taught, and prayed in the absence of a full-time minister.

“They kept the church going,” said Ruby Bright, retired chief executive officer of the Women’s Foundation and daughter of Annie Lou.

“Both ladies married into the Saulsberry family. That’s how they ended up with the same last name. My mother married my Uncle Connie’s nephew, Ferl Saulsberry. That was my father,” Bright explained.

Louise’s role as a church leader seemed a natural springboard to working with voter registration. She wanted a better life, not only for her children, but “for all of God’s people.”

“I would go into the home and talk to them about voting,” Louise said.

She continued, “Some thought because they didn’t own any land, or because they were poor, they couldn’t vote. And, sometimes, they were just plain scared to vote. But I would tell them, ‘If you want change, then vote. But, if you want things to stay just like they are, then don’t vote.’”

Despite warnings, intimidation, and outright threats from whites in leadership, Louise refused to stop.

A new day was dawning in Mississippi because African-Americans began to understand the power of their vote.

Louise would pay a heavy price for not backing down — the imprisonment of her eldest son, Larry Saulsberry.

He was arrested for possession of a small amount of marijuana, which might have otherwise warranted a few months in jail and a nominal fine. Larry Saulsberry was sentenced to 28 years.

“It was their chance to pay my mother back,” said Katie Saulsberry. “My brother was sentenced to 28 years. He served 23.”

Year after year, Louise Saulsberry petitioned the judge to reduce her son’s sentence, but she was repeatedly denied.

“This was a praying mother, and she was undeterred by their denials,” said Bright. Aunt Louise tried to get Larry released for more than 20 years. Larry was finally released after 23 years.”

Larry Saulsberry would only live 18 months as a free man. His death was a source of great sorrow, especially to his mother.

Now, Louise finds immense joy in spending time with her children and their children, and generations beyond them.

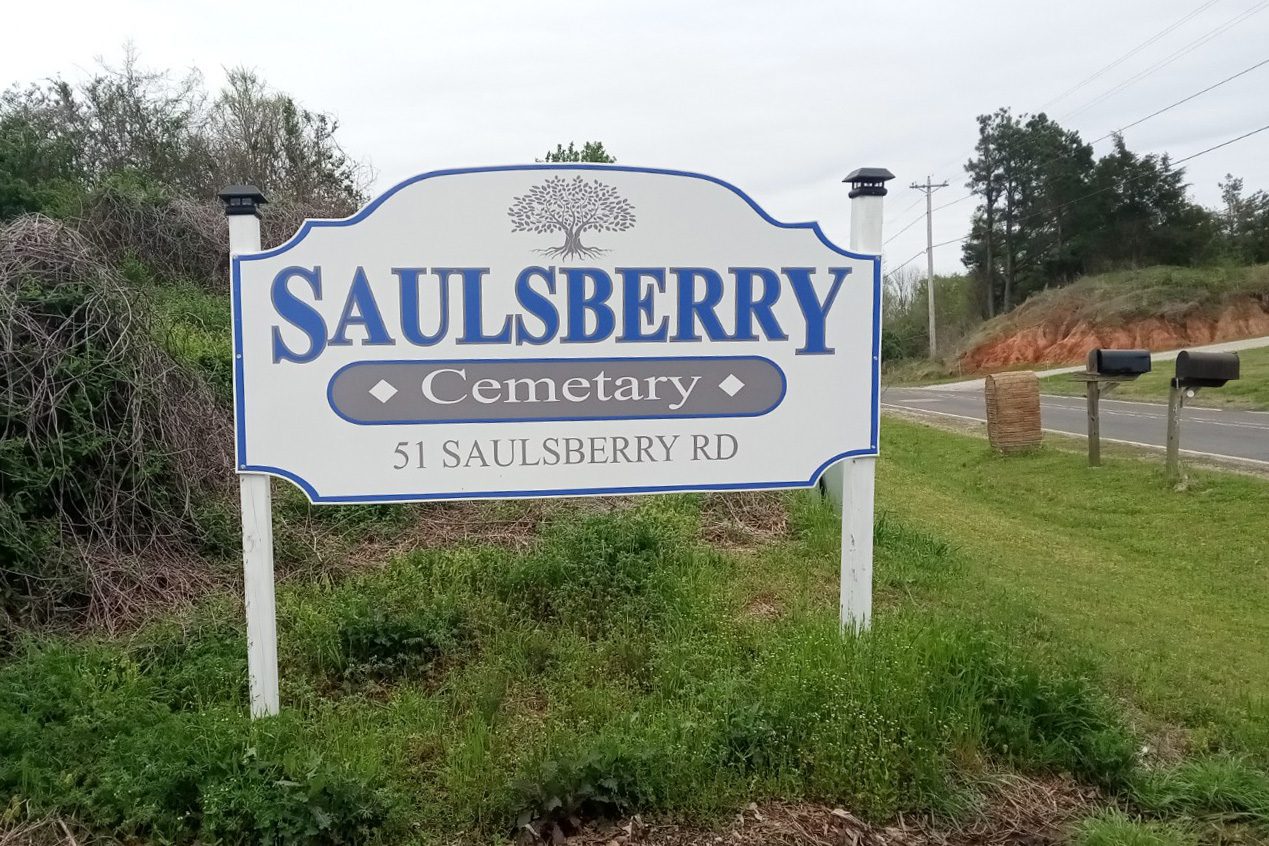

Family lore says that somehow, two of the Saulsberry men actually got their 40 acres and a mule. Those 80 acres grew into many more. Some sold their portion of land for a quick payoff.

But others learned to value the land from their ancestors.

“We understand that land is wealth, the inheritance of our parents and grandparents,” said Bright.

“Our children have been taught to cherish and value the land. When all else fails, they know they can always come back home because the land is our home.”