In the 194-year history of “the Black Press,” The New Tri-State Defender – in multiple forms – has lived 70 of those mission-driven years.

The beginning was a moment of courage born largely in response to a treacherous Jim Crow mindset that propelled white citizens forward with often deadly intent to block African-Americans’ pathways to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

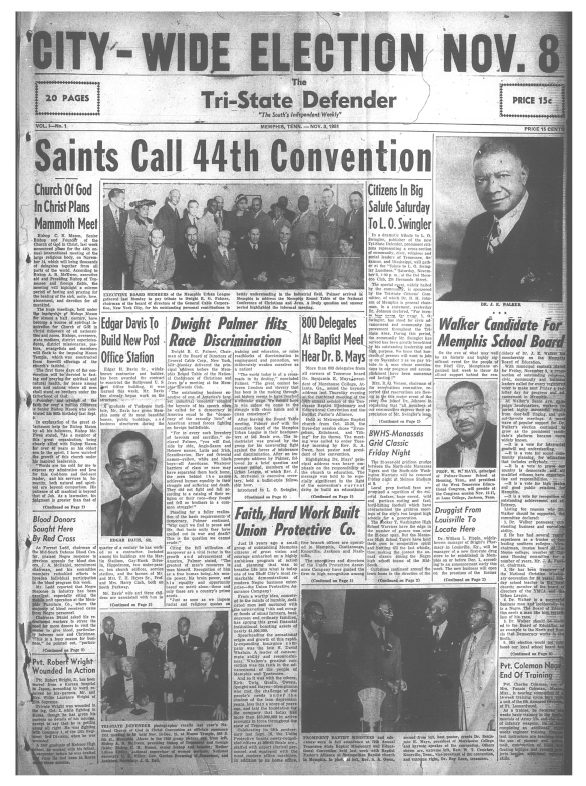

On Nov. 1, 1951, Lewis Ossie Swingler, who had been the editor of the Memphis World, was in charge as publisher and editor when the Tri-State Defender rolled out its first issue. A 10-point program on page six, the Editorial page, listed this as point No. 5:

“To uphold the principle of equality of opportunity in employment, education, politics, and all fields of human endeavor.”

A single issue was 15 cents. Subscription rates were $6 for a year, $10 for two years. Also available was a special introductory offer: seven issues for $1.

Billed by self-description as “The South’s Independent Weekly” and birthed to serve “1,000,000 Negroes in the Tri-State Area,” the Tri-State Defender set forth to be “an expression of the desires and needs of the community.”

Its founder was John Herman Henry Sengstacke, who at one point owned the nation’s largest chain of newspapers focused on African Americans. A civil rights advocate, Sengstacke in 1940 formed the National Newspaper Publishers Association, which now has 230-plus members, including The New Tri-State Defender.

According to the first edition’s lead editorial, a newspaper is “only as great as its readers make it. Its strength comes from the energy pumped into it by the people. Its muscles and bones are the determination of the people; and its heart is the conscience of God-fearing men and women.”

The newspaper’s name – as detailed in that first editorial – was “chosen” by “you, the people …. It symbolizes the fulfillment of your hopes and dreams.”

With adept leadership in place, the Defender commenced with its effort to present a comprehensive look at the Black communities in the tri-state region. Included in its approximately 15 pages of text were news, pictures, cartoons, household hints, women’s and youth pages, sports and entertainment features.

Throughout the Defender’s inaugural year, the newspaper laid the foundation as a newspaper that was committed to being at the pulse of the tri-state region’s Black communities. Always with racial progress at the core, the Defender featured stories ranging from Memphis as a rich African-American cultural center to courageous individuals who challenged the racial status quo of the era.

Not restricted to what happened locally, the Tri-State Defender brought news of segregation cases that happened all over the nation to its readers. Impressively, the newspaper pointed out how Black citizens of the tri-state region were pioneers in forcing racial improvements despite the racial mores of the South. The best example in the 1950s was the local response to the U. S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision that reversed the “separate but equal” doctrine on May 17, 1954.

The Tri-State Defender captured the sentiment of the time in its November 6, 1954 newspaper:

“We welcome the decision of the Supreme Court and look upon it as another significant milestone in the Nation’s quest for a democratic way of life and in the Negro’s long struggle to become a first-class citizen…This is part of an evolutionary process which has been going on in the South and the Nation for some time.”

The Tri-State Defender’s ability to keep the progress of the race at its core yet remain a newspaper that included all aspects of the African-American community was reflected in how the newspaper connected sports and desegregation. In an article entitled, “Integration is a Two-Way Street,” the Defender reminded its readers that African-American people had a responsibility to initiate integration attempts as well.

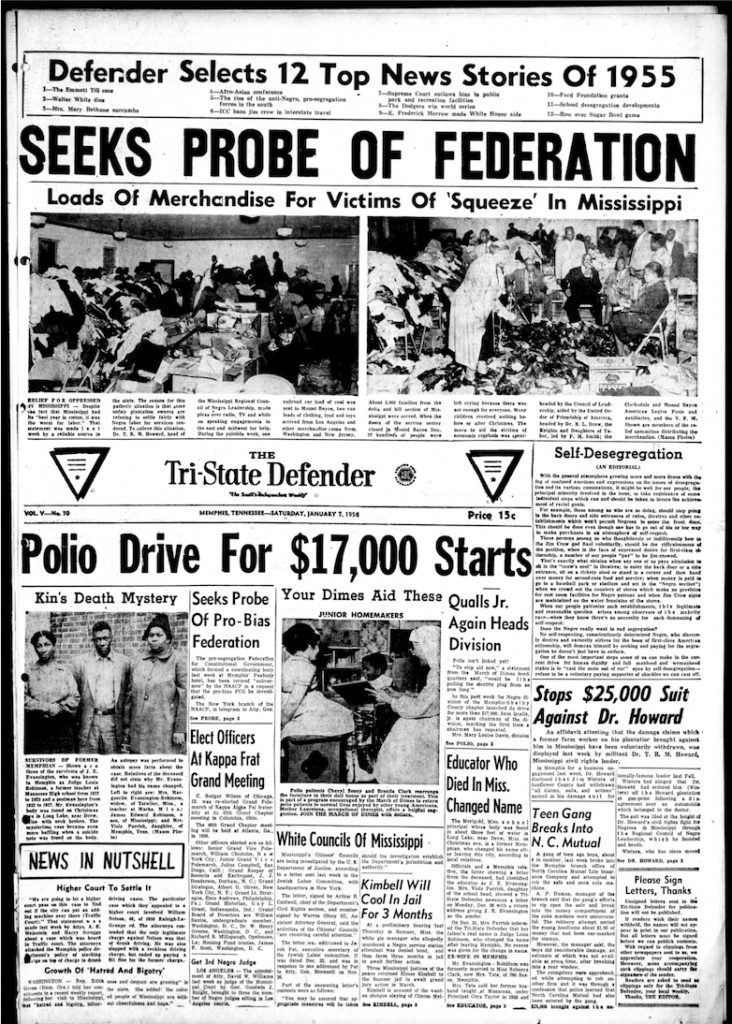

The newspaper showed how sports took the lead with several Black colleges competing against white schools on the gridiron. And when banks throughout the state of Mississippi put a “freeze” against loaning African Americans money to buy homes and start businesses, the Tri-State Defender encouraged all to join an effort to raise funds for those denied credit in their own state.

African Americans in Memphis and throughout the country were hopeful that comprehensive racial discrimination was a practice of the past, yet they soon found out many more battles would have to be fought nationally and locally.

African Americans in Memphis and throughout the country were hopeful that comprehensive racial discrimination was a practice of the past, yet they soon found out many more battles would have to be fought nationally and locally.

The most memorable incident to remind Blacks that their status had changed little by the mid-1950s was the gruesome death of young Emmett Till in Money, Miss. For Memphians, the proximity of Till’s “lynching” and the Tri-State Defender’s vivid portrayal of his open casket reminded them that they too were subject to the region’s racial violence.

Despite the troubled times, Black Memphians persevered with a renewed vigor and relentless spirit that would fuel their fight for better conditions. Over the next few years, the Defender highlighted the arrival of several “freedom fighters” in Memphis.

By the end of the 1950s, the atmosphere necessary for confrontation was evident among Memphis African-Americans and in the pages of the Tri-State Defender.

The demands of Memphis’ African-American community chronicled in the Tri-State Defender foreshadowed the events of 1960. Beginning with the Emancipation Proclamation anniversary, Memphis’ African Americans pushed for what they described as “real emancipation to Negroes.”

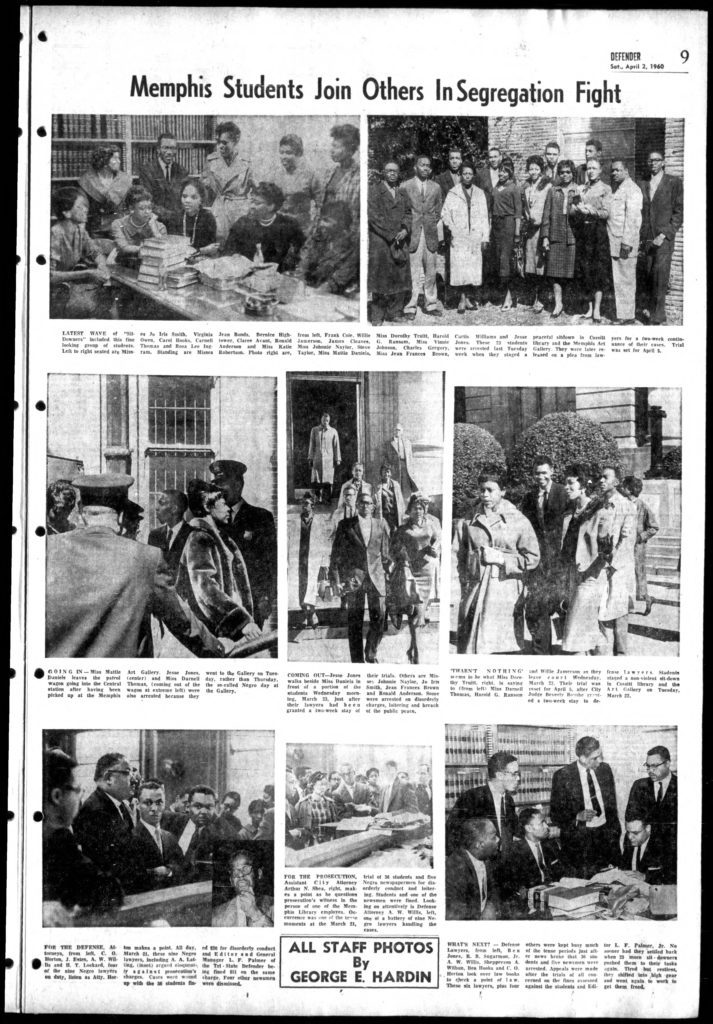

At one point, Tri-State Defender writer Burleigh Hines, chief photographer George Hardin and others reported that they were denied admittance to the Auto Show at Ellis auditorium, having been told by policemen that “Colored can’t come in here today.”

The incident sparked a flood of letters to the Defender and widespread outcry by African Americans. Although many were initially frustrated because they owned automobiles valued at an estimated $50 million but could not view these particular cars, their refused entry to the Auto Show sparked them to attack segregationist practices in bus seating, the library, eating facilities at most public places, and schools.

Among the myriad efforts to overturn segregation, the Tri-State Defender staff was involved in one particularly impressive example. Alongside approximately 60 students from LeMoyne and Owen colleges, the entire Tri-State Defender editorial staff was arrested for attempts to desegregate the libraries at Cossitt and Peabody and the Brooks Art Gallery.

Along with the students, the Defender staffers were charged with disorderly conduct and fined for their actions. Editor and general manager L.F. Palmer had to pay a higher fine for his alleged leadership in the demonstrations.

Palmer and the entire Tri-State Defender organization received more intense repercussions shortly afterwards when a cross was burned on the front lawn of their office building.

A few weeks after his arrest, Palmer received a citation from Capital Press Club of Washington, D.C. for his distinguished service in mass communication. That small but significant victory for integration was tempered by the death of award-winning journalist L. Alex Wilson – renowned as the man physically assaulted outside of Central High School during Little Rock’s desegregation attempt in 1957.

Wilson’s presence at Central High School epitomized the courage and passion that he consistently demonstrated as the Tri-State Defender’s editor and general manager and later editor-in-chief for the Chicago Daily Defender.

Grandson works to amplify legacy of tenacious TSD editor who refused to run

Progress in the struggle for racial equity did not come any easier after 1960, but many African Americans and the Tri-State Defender remained on the front lines.

In an effort to test desegregation in restaurants, Tri-State Defender reporters M.L. Reid and William Little visited several places to see if they would be served. As expected, they received mixed reactions, but their presence made a statement that African Americans in Memphis and the Tri-State Defender were watching closely.

Not everyone welcomed the presence of the Defender. While photographing a demonstration after the assassination of Mississippi civil rights leader Medgar Evers in mid-1963, Ernest Withers had his coat ripped off, was beaten with a nightstick and had the film in his camera deliberately exposed by policemen. Nonetheless, like his colleagues at the newspaper, Withers never backed down from his responsibilities as a newspaper photographer.

The people’s perseverance combined with the support of the Defender would remain critical in the tumultuous times during the mid-1960s forward.

The Tri-State Defender continued to be recognized on the national scene throughout the middle and late 1960s. The most prominent example was the nomination of John Sengstacke to the National Alliance of Businessmen’s Executive Board by President Lyndon Johnson. The 15-member group advised the government on ways to cope with unemployment.

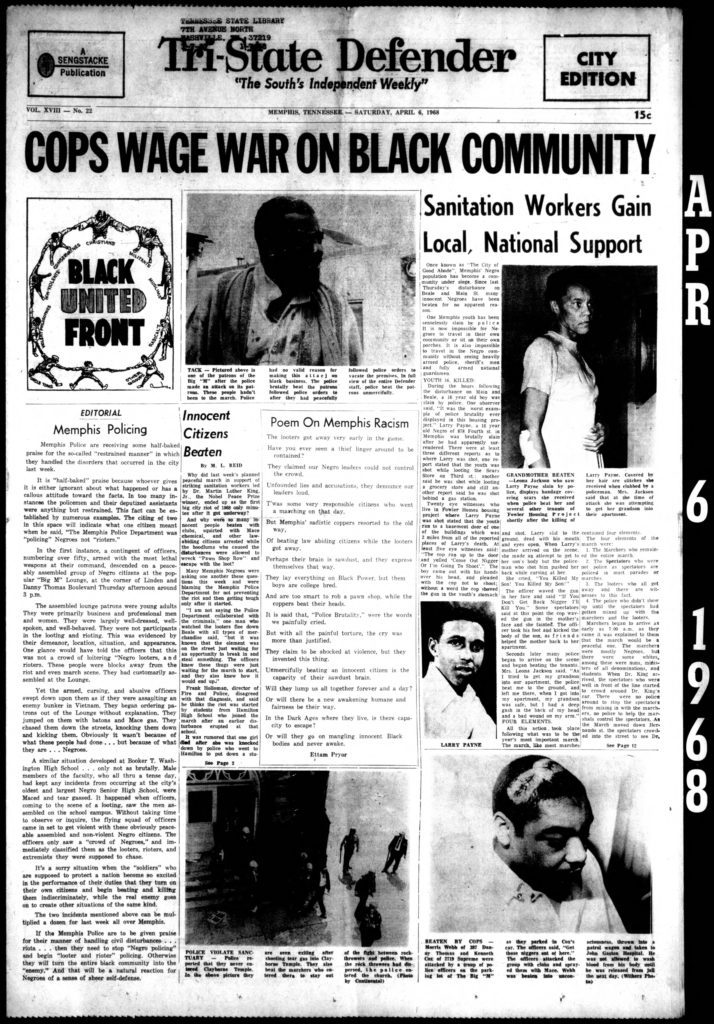

As the only African-American selected, Sengstacke’s presence was important for the consideration of African-American concerns. In particular, Sengstacke’s appointment was critical for morale as citizens offered their support for the emerging sanitation workers’ strike in Memphis.

The presence of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. garnered national notoriety for the strikers, yet the momentum from this attention came to a crashing halt with King’s assassination on April 4, 1968.

The presence of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. garnered national notoriety for the strikers, yet the momentum from this attention came to a crashing halt with King’s assassination on April 4, 1968.

The entire world stood still until the “King” was put to rest. After a period of grieving, the resiliency of African Americans in Memphis had them back fighting for Dr. King’s dream later in the year.

The tumultuous times of the 1960s caused many people to question whether continuing the fight for justice was worth the consequences. Yet as the Tri-State Defender reminded its readers, the unforgettable assassinations of prominent Civil Rights leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Dr. King were all that the people needed to “keep on keeping on.”

Those who marched with Dr. King in Memphis included a young educator named Willie W. Herenton, who became Dr. Willie W. Herenton, the first African American to run Memphis City Schools and later the first African American elected Mayor of Memphis. TSD chronicled the evolution of Dr. Herenton, who became the longest serving mayor in the city’s history.

John Sengstacke passed in 1997 and the company’s assets were placed in a trust and sold to Detroit-based Real Times Media (RTM) in 2003.

Seven years later, Bernal E. Smith II, a Memphis entrepreneur with deep community roots, was named publisher of the Tri-State Defender. In October 2013 — and for the first time in its storied 62-year history — the Tri-State Defender became locally owned and operated.

RTM sold the assets of Tri-State Defender, Inc. (TSD) to BEST Media Properties, Inc., a Tennessee Corporation established by Smith and backed by a local investment group that became its board of directors.

Smith set an accelerated course forward into the digital and multi-media age.

“The TSD is a great brand with significant historical meaning and respect throughout the Greater Memphis community,” said Smith. “We plan to leverage the brand for future growth and impact here in the Mid-South and ultimately on a global basis.”

As headlines about police brutality and discrimination resurfaced, Smith pushed the newspaper to continue going beyond just reporting the news.

“We’re getting into the issues and in some instances really being a tool for change,” he said.

Tragedy struck toward the end of October 2018 when Smith, who had significantly raised the newspaper’s public profile, died at his home at age 45. The ownership group stepped forward, with individual members taking on specific tasks. The TSD’s news operation continued steadily under the direction of Executive Editor Karanja A. Ajanaku, who preceded Smith at the newspaper and had been named associate publisher shortly before Smith passed.

As the newspaper-turned-multimedia company dealt with its internal evolution and moved forward, the world was hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. The TSD pivoted, converting to a mostly remote-based operation and jumped full bore into providing the community with solid, news-you-can-use information to navigate through the public health hazard.

Now 70 years old, the TSD is positioned to build upon the vision of Smith and of the Tri-State Defender’s founders. The fact that what once was called the community’s “baby” is still about the business of service seven decades later is a testament to the need and its roots.

“In this environment when a number of newspapers are dying, we are celebrating the continuity and strength of TSD in this community and the Black Press in general,” said Calvin Anderson, president, Best Media Properties.

Beginning with this special edition on the week of the Tri-State Defender’s founding and continuing for the next year, the TSD will showcase its body of work over the years while renewing its commitment to be a valued voice in the region.

(This story reflects the research of Dr. Russell Wigginton and the Memphis Branch of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History.)