Many know Perry Eugene Wallace Jr. as the first African American to play basketball on scholarship in the Southeastern Conference (SEC). For me, he was a bigger-than-life extension of my family tree.

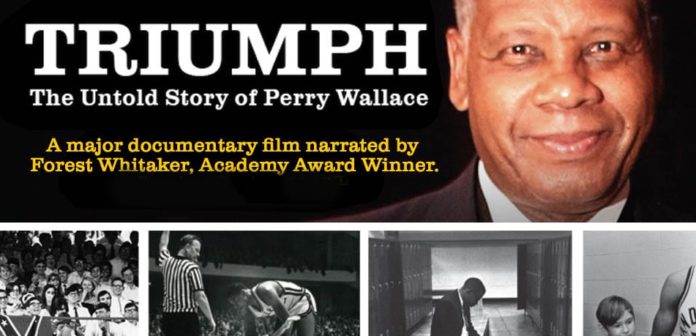

Those two facts recently contributed to me being on stage at the National Civil Rights Museum for a panel discussion follow the screening of “Triumph: The Untold Story of Perry Wallace.”

Perry, who played for Vanderbilt (1967-70), became a lawyer and law school professor. He died on December 1, 2017 at age 69. His life is chronicled in the book “Strong Inside: Perry Wallace and the Collision of Race and Sports in the South.”

A movie was being produced about Perry’s life when he passed away just before his 70th birthday. At the recent movie screening of the 2017 film, his now 80-year-old sister (my aunt), Jessie Wallace Jackson, who has advocated for her brother as long as I can remember, sat down front looking up at me and the discussion panel.

There is a longer version of “Triumph,” but the screening version was about half an hour. It was a gripping and authentic portrayal of how things were back then: young blacks – men and women – being accosted by police dogs and night sticks; crowds of angry, white faces shouting epithets and worse; kids amidst the crowd as hatred is spewed at black people.

It was especially difficult for Perry when the Vanderbilt team played at the University of Mississippi. Fans would scream the n-word at him and throw things onto the court while he was at the free throw line.

At one point in a game against Ole Miss, he was bloodied by what he felt was an intentionally thrown elbow that was neither called or acknowledged by the referees. One of the trainers took him to the locker room holding a towel on his face. He was temporarily blinded in one eye.

When the bleeding stopped and he regained his sight, Perry looked around and realized that he was the only one in that locker room. The game had resumed, and he was left to take the lonely walk down the corridor back onto the floor.

He recalled the moment: “When they saw me, the whole place went crazy. ‘Oh, n****, you back for some more? Well, we got some more for you.’”

Perry remembers another time when the team had to play in Mississippi. The locker room they were given was strewn with trash and human excrement.

Ironically, Perry played his last game at Ole Miss. He was honored and presented with a gold commemorative trophy. Footage shows a young Wallace walking across the gym floor to receive his award, and the Ole Miss crowd gives him a standing ovation.

Four years had passed. He had endured and other African-American players were blazing their own trails in SEC basketball and football.

The panel discussion followed immediately after the film’s screening. On my far left was Dr. Derrick Payne, a dentist who graduated Vandy in 1993. He played football at both Hamilton High School and Vanderbilt.

To my immediate left was Bertha Rogers Looney, one of the “Memphis State 8,” who integrated the now University of Memphis. And sitting on my right was legendary high school and college coach Verties Sails.

Seeing the movie for the first time, Dr. Payne said, “It dawned on me that Perry Wallace gave me the opportunity to go to a college like Vanderbilt University and play football. …I was a little choked up watching it because as an athlete, I really didn’t have to go through what he went through…I thank God for Perry Wallace.”

The loneliness and isolation that Perry expressed as he remembered his years at Vanderbilt were painfully familiar points of reference for UofM trailblazer Looney.

“I know about the loneliness he’s talking about,” she said. “We couldn’t be on campus past noon, and our classes started at eight. We weren’t allowed in the student union or the cafeteria. We were only allowed in the library. And being escorted to and from class by a plain-clothes police officer was lonely, very lonely.”

Coach Sails, now in his late ‘70s, recalled the sobering details of becoming the first African-American full-time assistant coach at a major university in the South while at the Memphis State. That included the recruiting experiences of high-school basketball phenoms Larry Finch and Ronnie Robinson and the promise he had to make to Finch to come straighten things out if the experience at Memphis State went awry.

In addition to my family connection to Perry, I found my way onto the panel as the recipient of the first creative writing degree awarded by Vanderbilt. I talked about what I did not want to talk about. And that was a college professor and his diatribe about how, “It wasn’t my fault, but my brain was not as developed as my classmates.”

Yep, black people’s brains were not as big as white people’s brains, professor Frank Sullivan said, adding that I should steer clear of creative writing as a degree choice. I still remembered the humiliation of that moment. Yet not only did I earn Vandy’s first creative writing degree, God helped me do it in three years.

Perry was drafted in the fifth round of the NBA Draft, but opted for a law career. He graduated from Columbia Law School and championed environmental justice. He spoke French fluently and sang opera – a quintessential Renaissance man.

Race provided the backdrop for Perry’s journey to success and Coach Sails’ put the issue’s ongoing challenge in this context:

“If we get to know each other, if we trust each other, if we do the right thing with each other, every thing will work out alright,” he said.

“We’re so busy running from each other, we don’t take the time to meet and greet each other and find out if we can help one another. But we’re all brothers and sisters under God. God is our leader. He is the Shepherd, and we are the sheep. When we get that through our heads, then we’ll be a whole lot better off.”