In July, Art Gilliam was inducted into the Tennessee Radio Hall of Fame … just outside of Nashville in Columbia, Tenn. He was excited, yet he took it in matter-of-factly.

“In the sense that anything that I can do that actually helps project the image of what we do as far as WLOK is concerned, is always good,” Gilliam said in an interview with The New Tri-State Defender before the awards ceremony. “And of course from the standpoint of we put in a lot of years in radio, so it’s nice to be recognized….

“The fact is though, that no one person is really getting into a hall of fame by themselves. … I’m happy for our whole organization more so than just for me personally.

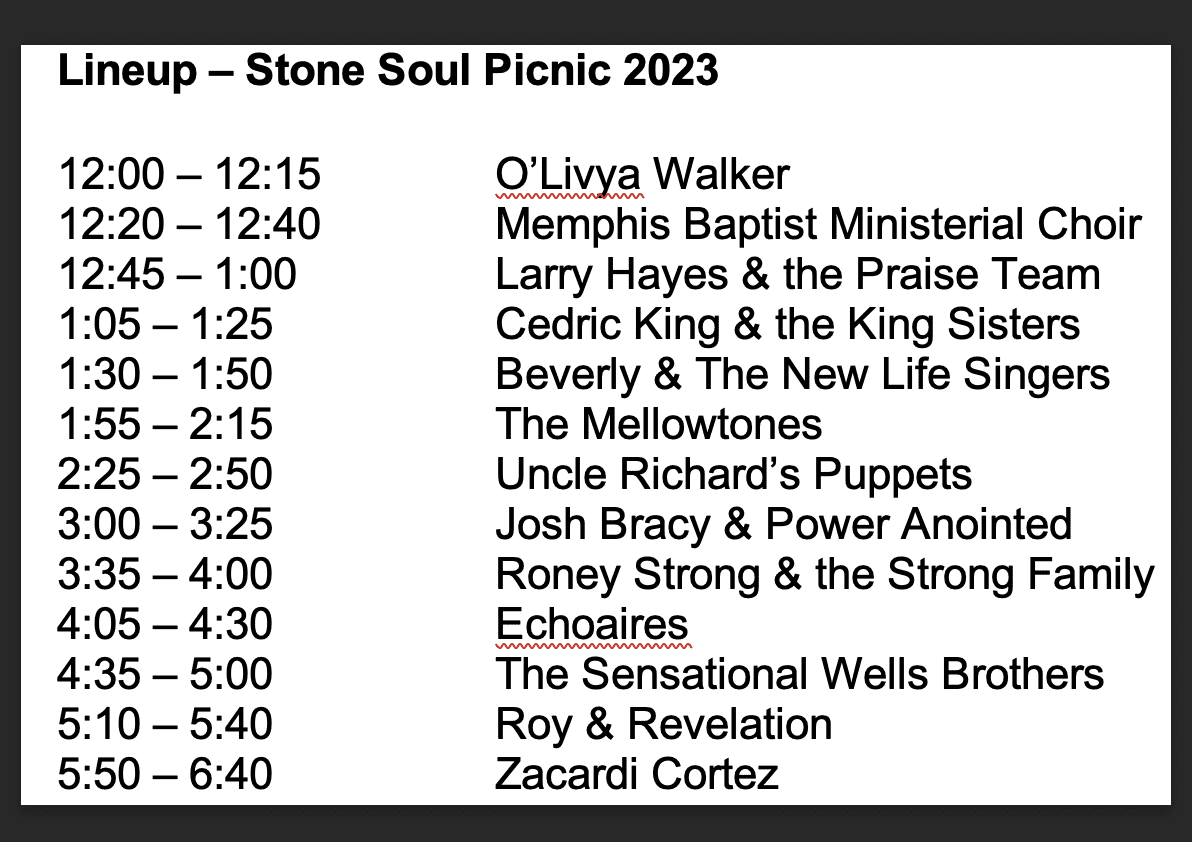

It’s remembrance time for Gilliam, 80, and WLOK. The 2023 WLOK Stone Soul Picnic will be Saturday, September 2, from noon to 7 p.m. at the Memphis Music Room. It is a free event with a significant lineup of national and regional artists.

Gilliam agreed to travel memory lane during a conversation in WLOK’s Downtown office. His first remembrance of radio was “me, mom and dad, grandma sitting around the radio. … This was before there was television. … It was one of those old-fashioned radios … and we were listening to Joe Lewis fight.”

He was about nine. The family lived in Nashville. Radio was a family magnet.

Gilliam’s mother was a school teacher from Nashville and had attended Tennessee State University before Columbia University in New York. She graduated and returned to Nashville to teach.

His father was from Newbury, South Carolina. He had attended high school but was not college educated.

“His experiences more came through, I guess the school of hard knocks going to New York and being a Pullman porter and doing a lot of odd jobs along that line because his parents passed away when he was younger,” said Gilliam.

The elder Gilliam landed in the insurance business and ended up in Nashville. He progressed up from a debit and eventually became vice president of sales for Universal Life Insurance Company, and moved the family to Memphis. Ultimately, he became a second vice president at Universal Life Insurance Company.

Gilliam was about 10 when the family moved to Memphis. His mother taught began teaching. He attended Hamilton and in the 10th grade was sent to a prep school in Connecticut.

“It was a culture shock … going from the all-black Hamilton, segregated south … And I was the only black student in the class … a small school of 40 people in each class …”

His parents, said Gilliam, likely thought sending him to the prep school would be greater educationally.

“That was also around the time that Emmett Till was killed in Mississippi as well. … I wasn’t privy to all the discussions about why (he was sent), and in those days you didn’t question. … They told you what to do, you did it. …”

After prep school, he went to Yale University, where he was one of five African-American students in a class of thousand.

With his dad in the insurance business. Gilliam looked to follow suit. He earned a degree in economics and focused on become an actuary, later getting a master’s in actuarial science at University of Michigan.

The military draft was in effect, so Gilliam volunteered to go into the reserves, served six months and committed to a seven-year reserve obligation.

After securing his master’s degree, Gilliam returned to Memphis and began work as a debit agent for Universal Life Insurance Co. in Dixie Homes. Later, he worked in the claims department. He was at universal until 1974, including 1968 when Dr. King was killed in Memphis.

In 1974, Harold Ford Sr. was serving as the U.S. Congressman from Memphis. Gilliam, who had made Ford’s acquaintance, became his administrative assistant and headed to Washington, DC.

By this time, Gilliam had blazed a trail at The Commercial Appeal, where, in 1968, began writing opinion columns. He had approached the editor, making that point that the newspaper didn’t have any representation of a Black point of view.

From ’68 to ’74, Gilliam wrote op-eds, the first about the sanitation workers strike. Eventually, WMC-TV approached him about being on television and he was hired as the weekend anchor.

In the early part of ’76, Gilliam moved on from Washington.

“At that point, I had gotten involved in wanting to purchase a radio station. … For me, radio, I always liked radio because radio is closer to its community.”

During that period, radio in the African-American community, of course, involved W D I A, the first radio station in the country oriented toward a Black audience. There were no more than a dozen stations in the whole local market.

“My interest was in getting involved in the community, really the fact that radio had such an opportunity to be helpful to your community. … I thought it was good business, but my primary interest wasn’t in the business aspect of it…”

When he and an ownership group bought the station in 1977, he did not realize that the previous owners had put Operation PUSH off the air.

“You may recall Operation PUSH was considered a militant organization at that time … I didn’t find out until after we had closed the deal (that) they had been pushed off the air.

Among the first moves was restoring Operation PUSH.

Gilliam’s initial interest in radio ownership came as Memphian Benjamin L. Hooks served on the Federal Communications Commission. He talked with Hooks, who linked him with a broker aware of an opportunity in Memphis. It was WLOK.

Gilliam spent about a year and more putting the financing together.

“It was $725,000 as I recall. And I had a total of 750,000 bucks. … By the time I got through getting everything together, I had $25,000 in working capital to deal with a $725,000 purchase. So it was pretty tight.”

Excited, Gilliam knew he had to “do a lot of on-the-job learning,” benefitting from people already at the station, Melvin ‘Cookin’ Jones.

The radio deal was consummated in February of ’77 during Black History Month.

“We were the first African-American-owned radio station and the first locally owned.… It had a profitability, but there were some challenges that they were facing for sure. … we did a lot of upgrading. And I mean, just as a physical plant, that alone.”

With the induction into the Tennessee Radio Hall of Fame as the backdrop, Gilliam fielded a question:

“What stands out to you relative to that journey? I mean, now that you’re here and looking back, what stands out to you?”

Said Gilliam: We’ve accomplished a lot of the things we wanted to accomplish in terms of being a positive influence on the community in terms of people who listen to us. We have some very, very loyal listeners. And so, W L O K becomes a catchword, something that’s avery positive for them….”

WLOK, he said, provides an outlet for “certain things … you are not going to see in the same way anywhere else. The opportunity for those who are opposed to what’s going on in the society to be able to express that, we offer that as a central part of what we do.

“But we’re basically a music station. Radio is essentially music. People listen to radio for music…. We are a gospel radio station, but we consider ourselves a community station as opposed to a religious station.”

WLOK is “still a religious station in the sense that the majority of our listeners are Christians and church-going Christians,” said Gilliam. “But the thrust of what we provide is a broader experience than simply we’re playing music and talking about Christianity.”

Along the way, an FM component was added. Community connections have been strengthened through the annual Stone Soul Picnic.

And now there is the Black Film Festival, this year being the seventh.

Taking in the entirety of the journey, Gilliam said, “… it’s a long way from the back of the bus by law to the Radio Hall of fame.”

The Radio Hall of Fame, Gilliam said, wasn’t something that he thought about along the way, other than thinking that “W L O K ought to be in the Hall of Fame. I had thought that because of the history of the station, and we are a Tennessee historical landmark also….”

Gilliam has been in the radio business 40-plus years and married for 18 of those years. His wife, Dorrit, was a tutor in Denmark. They met via the Internet.

“Well, when she first moved here, she was in a tutoring program over at Booker Washington High School. … they closed down the tutoring program, and we happened to have, at that time, someone who left here who was in radio traffic. So, I said to her, ‘since you’re not tutoring right now, we got this opening.’ …

“She learned so much about radio that she is really became like, you might say, a partner, but not because we started out that way, but because just by happenstance. That’s one of the best hires I ever made … getting her involved because she’s done such a great job….

What’s the future for W L O K?

“My hope is that W L O K can continue for an ongoing period as far as the radio part of what we do to be a community voice as we have been … but also be able to have a black-owned business that is successful; That’s ongoing.

“ … there are challenges that all businesses face, but that small and minority businesses face even more so.”

A big part of WLOK now is making sure “that the people who are here, who wish to go forward, and many of them have a sense of pride about the fact that it’s a Black business, but they’re not all Black. But they have a sense of pride about that. … We’re trying to bring in people who have that spirit.”

As for Black radio in general, Gilliam said, “The state of Black radio is that stations like us are the exception, and therefore it’s challenging to make that go forward. But yet it’s important. The state of Black radio is, a lot of people that I knew who were in Black radio in the beginning are no longer in radio.”

Meanwhile, he continues to crank out editorials.

“I’ve got to reflect the attitudes and views that you see within the Black community, but I also try to get people to think about what the subject is, whatever that thing is, and to pose something that they (think) about.

“But essentially, the editorials are reflective of the point of view of our community to a great extent. You try to reflect that, but also try to get people to think about issues.”