A few yards across from the parking lot of an all-boys Memphis school lies a small, tree-lined courtyard, where a class of eighth-graders studies a large historical marker.

The new marker tells them that children were sold as slaves in this spot. An older, nearby marker had failed to tell the whole story — Nathan Bedford Forrest, the subject of the marker, made Memphis a hub of the slave trade near that busy downtown corner.

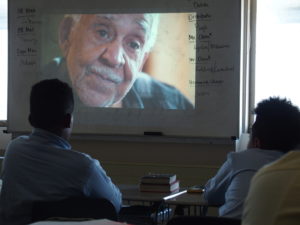

The boys at Memphis Grizzlies Preparatory Charter School, who are nearly all black, earlier learned about the painful legacy while watching an episode of “America Divided,” a documentary series featuring celebrities exploring inequality across the nation. The episode featured the Memphis campaign that eventually removed a nearby statue of Forrest, a Confederate general, slave trader, and early leader of the Ku Klux Klan.

Being so close to such upsetting history that only recently has bubbled to the surface of public display was a lot for eighth-grader Joseph Jones to take in.

“I can’t believe that this history is right outside our school,” he said. “I think I barely know what happened in Memphis. So many things that I don’t know, that I need to know, and that I want to know, happened in this very city.”

Lately, Memphis — along with several other cities in the South — has been grappling with how tell the complete stories of historical figures who many felt were war heroes, but who also contributed to the enslavement of black Americans.

The new and larger historical marker about Forrest was erected on the 50th anniversary of the assassination of civil rights icon Martin Luther King Jr. He was killed two miles from the all-boys charter school. City leaders vowed and succeeded in taking down Forrest’s statue, which had loomed downtown for more than 100 years, before honoring King’s legacy.

From the archives: Meet the Memphis educator leading the charge to take down her city’s Confederate monuments

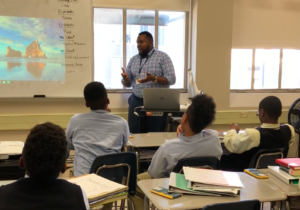

Tim Green, a teacher at Grizzlies Prep, prompted discussion among students about how to use their newfound knowledge about history in positive ways to improve their city. It’s part of Green’s larger effort to teach students how to express their feelings on difficult topics.

Recently, that has meant delving into the city’s racial history, which is fraught with tragedy that has not been fully reckoned with in public discourse.

“Me forming this class was a way to talk about some of things we deal with and one of those things is our past,” he recently told students. “As African-American men — and African-Americans in general — we don’t have a clear understanding of where we came from.”

Students said their initial feelings after watching the documentary included anger, sadness, and fear.

“It kind of makes me feel scared because you know your parents and your teachers say history repeats itself,” said student Sean Crump. “So, we never know if it’s going to happen again because some things that people said are going to stop have came back. … That makes me feel scared of when I grow up.”

Watching the documentary was the first part of the class’ history exploration before meeting with two key people who organized the removal of Forrest’s statue at the county government building about two blocks from the school.

The documentary shows actor Jussie Smollett interviewing the younger brother of Jesse Lee Bond, a 20-year-old black sharecropper. He was killed in a Memphis suburb in 1939 after asking for a receipt at a store owned by a prominent white family that depended on the credit balances of its black customers.

The brother, Charlie Morris, said he was ready to go on a revengeful rampage after learning his brother had been shot, castrated, dragged by a tractor, and staked to the bottom of a nearby river. He said he still carried the trauma, but doesn’t carry the hate he felt nearly 80 years ago.

“The first step to equal justice is love. Where there’s no love, you can forget the rest,” he said in the documentary. Morris died in June at the age of 98.

After the episode ended, the class was silent for a moment. The first question from a student: Were the people who lynched Jesse Lee Bond ever convicted?

The answer made one student gasp in shock, but was predictable for anyone familiar with the history of lynching in America during the Jim Crow era that legalized racial segregation. Two men were charged and tried for Bonds’ murder, but were quickly acquitted.

Students seamlessly tied the past to racism and violence they see in their city today.

“I feel sad because there’s lynchings and people — mostly white Americans — they know there’s lynchings and they know what the Confederacy did to cause those,” said student Tristan Ficklen.

“I would have felt the same too because all he asked for was a receipt,” student Jireh Joyner said of Morris’ initial reaction to Bond’s death. “And now these days there’s still police brutality and it’s hurtful.”

The post How Memphis students came face to face with the painful history in their school’s backyard appeared first on Chalkbeat.