by Laura Faith Kebede —

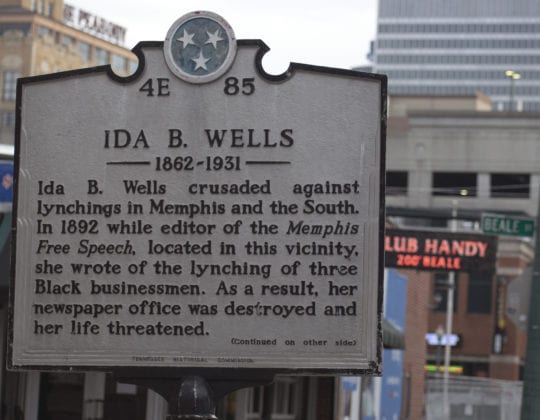

This week’s statue unveiling for Ida B. Wells is not the first time Memphis attempted to honor the famed journalist and suffragist with a landmark.

In 1931, the year Wells died, her long-time friend and fellow activist Julia Hooks pushed for Memphis leaders to name a new park built for African Americans after her.

White vigilantes had driven Wells out of Memphis nearly 40 years earlier after she wrote scathing articles revealing that white mobs used false accusations of Black men raping white women as an excuse for lynching.

Selma Lewis and Marjean Kremer, who together wrote a biography of Hooks, “Angel of Beale Street,” documented Hooks’ desire to name the park after Wells in a series of interviews with those who knew Hooks.

Hooks had demanded George W. Lee, an influential Black Memphis politician at the time, persuade then-mayor Edward Hull “Boss” Crump to name the park after Wells.

It’s uncertain if the campaign to name the park after Wells went beyond those conversations.

The park eventually was named after W.C. Handy, the composer and musician who took blues to the national stage, and still stands today on Beale and Third streets.

But the desire demonstrates that Memphians did not forget Wells after she fled.

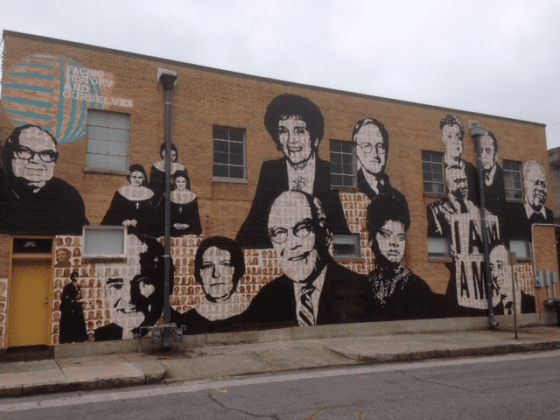

“Memphis didn’t forget Ida B. Wells. We’ve been preserving our history as Black people in Memphis for a long time,” said Earnestine Jenkins, an art history professor at University of Memphis, who has done extensive research on Black Memphis history.

Consequently, Hooks’ great-great-grandson Michael Hooks Jr. and his cousin and business partner Brent Hooks donated $1,000 to the Ida B. Wells statue effort help bring that desire to life 90 years later.

Julia Hooks, a Black woman, was a legend in her own right. She was a child prodigy musician and was one of the first women to attend Berea College in Kentucky.

She also taught white students there, which was extremely rare in the 1870s. After moving to Memphis, Hooks taught notable Memphis musicians such as W.C. Handy and Lucie Campbell.

Beyond music, Hooks was among the first to protest Jim Crow segregation laws in Memphis, a path Wells followed soon after.

Hooks also created the city’s first juvenile detention center for Black youth from her home and later opened a nursing home for Black Memphians.

She also was one of the founders of the Memphis chapter of the NAACP. Her grandson, Benjamin Hooks, was elected executive director of the national NAACP in 1977, serving at the helm of the organization until 1992.

He is the namesake of the city’s main library and the University of Memphis Institute for Social Change.

Julia Hooks, along with several other contemporaries in Memphis, such as millionaire Robert Church Sr., played a large role in Wells’ development as an activist.

“Ida B. Wells’ activism wasn’t created in a vacuum,” Jenkins said. “The community of Black activists in the city shaped her.”

Michael Hooks Jr. sees his contribution to the Ida B. Wells statue as a continuation of helping change the way Memphis commemorates its past.

Hooks’ engineering firm, Allworld Project Management, assisted the city and nonprofit Memphis Greenspace in removing the Confederate statues of Nathan Bedford Forrest and Jefferson Davis in 2017.

“We want to replace that history with our own history for the next generation to learn from,” Hooks said.

The statue of Wells will be unveiled Friday (July 16) morning on the corner of Beale and Fourth streets. For more information on the week’s events, visit www.idabwellsmemphis.org.