By Kashmir Hill, The Root

Terrance Everett has been on the wrong side of the law for most of his adult life. When he was 18, he had to register as a sex offender for having sex with a 15-year-old, because she was under the age of consent. In his 20s, he was, he says, “hanging with the wrong people doing the wrong things,” resulting in charges for drug possession and assault, as well as a conviction for distribution of cocaine. He spent a few years in prison, got out at age 33, and decided he needed to turn his life around. He got jobs that didn’t involve illegal activity—working as a bouncer at a club and as a supervisor at the Port of Wilmington in Delaware. But it all fell apart in 2016. Police threw a smoke bomb into his living room, detained his pregnant girlfriend, and sent him to prison for 15 years, all because of a photo posted to Facebook.

Everett, 41, loves social media. He is an avid user of both Facebook and Instagram, frequently posting memes, selfies, and an assortment of jokes about sex and his prowess at it. Judging from his number of connections (1,674 Instagram followers and 1,763 Facebook friends), he’s not terribly discriminating when it comes to making friends online, and in 2013, he became one of the many Americans who have unknowingly accepted a friend request from an undercover police officer.

Police have come to recognize the fertile hunting ground of social media and are covertly surveilling people and groups there with little oversight. We don’t know how many people have been targeted for undercover surveillance on social media because police departments don’t keep track in a public manner and prefer, in general, not to discuss it. They’re willing to talk about posing as kids online to snare sexual predators—a relatively uncontroversial undercover practice—but they’re far more secretive about targeting suspected gang members, protestors, and other “people of interest.” We reached out to dozens of police departments around the country to ask what their policies are when it comes to undercover Facebook police work and discovered that very few have any kind of formal rules governing it.

“Every high-tech crime unit has one,” a New Jersey officer who monitors suspected gang members and drug dealers with an undercover account told NBC News. “It’s not uncommon, but we don’t like to talk about it too much.”

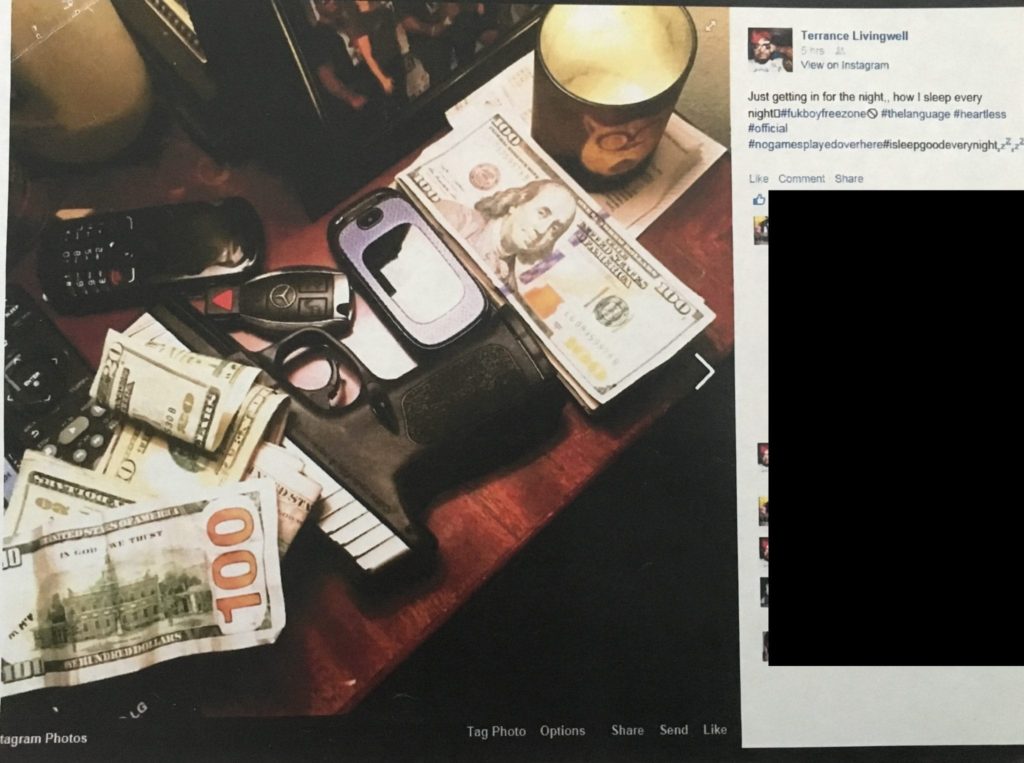

The police officer who friended Everett, Bradley Landis of the New Castle County Police Department, checked Everett’s account with surprising regularity. For more than two years, he checked Everett’s page one to three times a week, according to his own testimony. One Wednesday morning in November of 2015, his years-long online sting paid off. At 10 a.m., Officer Landis spotted a photo that had been posted to Everett’s Facebook wall five hours earlier of a nightstand with two cellphones, keys to a Mercedes, cash, and a handgun. It was captioned, “Just getting in for the night… how I sleep every night #fukboyfreezone.” Everett tells me he didn’t post the photo; his then-girlfriend used his phone to post it, he says, not realizing what the consequences would be. (“Fukboy” is a term that refers to having sex with lots of women, so the #fukboyfreezone hashtag was a reference to their monogamy.)

The screenshot Officer Landis took of Terrance Everett’s Facebook page

The screenshot Officer Landis took of Terrance Everett’s Facebook pageIn Delaware, as in many states, convicted felons are not allowed to own guns, so the photo set off an alarm bell for Officer Landis.

Advertisement

Everett deleted the photo by the afternoon, but it was too late. Landis had taken a screenshot. The next day, at 7:30 a.m., according to court documents, officers knocked down the front door of Everett’s house and threw a smoke bomb inside. Everett wasn’t there, but his pregnant girlfriend, Bianca Sencion, was in the upstairs bedroom. The officers brought her down to the kitchen, put her in zip-tie cuffs, and searched the house. The officers found the gun from the photo in the drawer of the nightstand it had been photographed on, but Sencion said it belonged to her, a claim later backed up by purchase records at Cabela’s. (A friend of Sencion also told me it was Bianca Sencion’s gun, that she had bought it because she was a stripper and felt she needed protection in case she was approached by an over-eager fan.)

Delaware authorities accused Sencion of making a straw purchase—buying a gun for someone who couldn’t do it himself—and charged Everett with “possession of a gun by a person prohibited.” Everett was convicted and given a 15-year prison sentence, which has to go in the record books as one of the worst outcomes ever for an ill-advised Facebook photo.

Screenshot: Trial testimony (Superior Court Official Reporters)

Regardless of who took the photo or who owned the gun, the bigger question is why Officer Landis had been stalking Everett on Facebook for more than two years in the first place, and was thus able to spot a photo that was live on Everett’s Facebook page for less than 12 hours.

At the trial, Officer Landis told Everett’s lawyer that he’d had the undercover account for three years and used photos from Google to populate it, but refused to reveal more, saying that it would “compromise other investigations.” Landis was never asked why he initially friended Everett. When I posed the question to Corporal Heather Carter, then-spokesperson for the New Castle County Police Department, she told me Landis had friended Everett because he was “known to police from his prior involvement with the police.” That suggests that he wasn’t a target of a specific investigation but rather subject to a dragnet surveillance operation.

Everett thinks he was monitored by the police department in retaliation for a 2013 YouTube video: “Cop pulls black guy over for nothing and gets dissed.” The video, starring Everett being pulled over for playing his music too loud, has over 1.2 million views. (The police department did not respond to a request for comment about this.)

In an August article in the Howard Law Journal, Rachel Waldman-Levinson of the Brennan Center for Media Justice took a deep look at the legal and policy dilemmas posed by law enforcement’s aggressive use of social media for policing.

Advertisement

“There’s always been the ability to do undercover work,” said Waldman-Levinson by phone. “But with modern technology it’s way easier to do. You just sit at your desk and send friend requests to 15 people and then check to see what they’re up to, as opposed to assuming a real world identity and attending meetings. Interacting with people undercover in real life entails a lot of risk, but online that’s not the case.”

In recent years, the Supreme Court has ruled that new technologies that make it easy for police officers to gather data about our physical movements—via GPS trackers and records of where we’ve been created by our smartphones—violate our constitutional rights unless police officers get warrants to use them. But unless law enforcement does something particularly egregious, as when the DEA stole a woman’s photos in order to impersonate her on Facebook, courts haven’t shown much concern about dragnet surveillance online.

Everett’s public defenders appealed his case to the Delaware Supreme Court, saying Everett’s Fourth Amendment right against unreasonable searches had been violated by being covertly surveilled on social media for years, but the court wasn’t sympathetic. The Court wrote that “the Fourth Amendment does not guard against the risk that the person from whom one accepts a ‘friend request’ and to whom one voluntary disclosed such information might turn out to be an undercover officer,” citing a 2014 case in New Jersey where a judge similarly decided that a burglar’s Fourth Amendment rights weren’t violated when an undercover cop started following him on Instagram without getting a warrant first.

But that was a case where the cops went undercover to investigate a specific crime—a string of burglaries in which the surveilled Instagrammer was a suspect. The judges who decided against Everett’s appeal didn’t seem concerned by the extended period of surveillance, nor the lack of an actual motive for the investigation. According to the Delaware Supreme Court, cops have the right to undercover-friend people on social media whenever they want for however long they want.

That means the only relevant law may be Facebook’s own.

“Our Community Standards require people to use their authentic identity and our standards apply to everyone on Facebook,” a Facebook spokesperson told me earlier this year, when asked about the company’s stance on the use of fictitious or undercover accounts by law enforcement. Facebook has written angry letters to the DEA and the Memphis Police Department after undercover work that drew media attention, but its guide for law enforcement didn’t explicitly instruct police officers not to misrepresent themselves on Facebook until last month.

(For the record, we’re not sticklers about Facebook’s rules here either.)

Absent federal or state laws that regulate “undercover friending,” it’s up to law enforcement to self-police their behavior on social media. In New Castle County, where Officer Landis works, individual officers get to make the call on covert digital surveillance.

“We have a policy for officers for their personal social media accounts. They can’t wear their uniforms or show pictures that are defaming the agency,” said police department spokesperson Corporal Carter by phone. “There is no policy for using social media accounts for investigation. It’s like handling a confidential informant. Each officer and detective handles it differently. You might do it one way and another might do it another way.”

Catherine Crump, a law professor at University of California-Berkeley, found that horrifying. “Our social media profiles contain sensitive, private information. The circumstances under which police access those profiles raise important public policy questions that should be decided in a transparent public process, not by police departments acting on their own and certainly not by individual officers make it up as they go along,” she said by email. “Police departments should have written policies explaining when they will go undercover to access our social media profiles. And those policies should be vetted by elected representatives, with input from members of the public.”

But leaving it up to individual officers is not unusual. We sent Freedom of Information Act requests to over 50 police departments across the country asking them for policies and training materials related to covert investigative work on social media. We chose the departments based on geographical diversity and news coverage of departments that have used undercover social media accounts. The vast majority of departments have social media policies, but most don’t address covert investigations. Their rules, in keeping with advice from the International Association of the Chiefs of Police, primarily address official accounts and personal use of social media by employees (e.g., “Don’t say racist things on Facebook”).

“That seems really problematic and ripe for abuse and misuse,” said Waldman-Levinson. “There needs to be a standard and oversight for what accounts officers create, who they friend, and how long they monitor them. Social media can be so incredibly contextual—it can be inside jokes, a lyric to a song that can be misinterpreted as a threat—and those risks are magnified because officers are monitoring people online with no oversight. They can see things online that they think mean something they don’t and that can lead to criminal consequences for the [monitored] person.”

Of the 43 departments that responded to our requests, just 13 have internal rules for undercover social media accounts in their police manuals. A handful of police departments refused to disclose anything to us because it “would reveal non-routine procedures.” The New York Police Department, for example, has bragged to the media about “pretending to be young women” on Facebook to friend suspected gang members, track troubled teens, and take down teen burglary rings. It claims in a Department of Justice research report to keep detailed logs about its undercover accounts, but it refused to provide documentation of its policies or practices for public review, and would not respond to a request for comment. We still counted it among our 13, based on what it told the DOJ, but we have no idea as to what’s allowed when an officer creates a fake account, who they can friend, how long they can friend them, or whether they ever need to end the friendship.

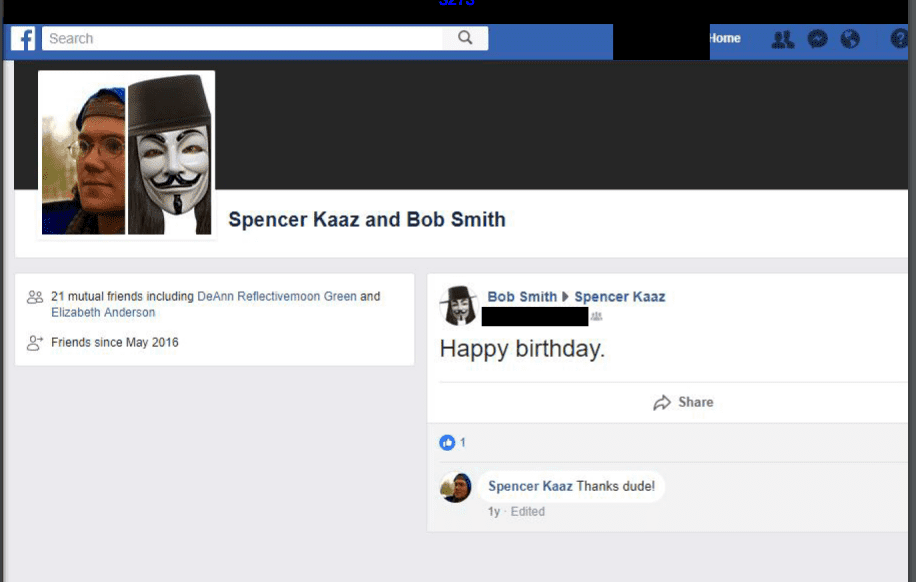

The unregulated nature of undercover social media police work leads to disturbing outcomes, such as the case of “Bob Smith” in Memphis, a fake Facebook account created by Memphis Police Department officer Timothy Reynolds to friend and monitor Black Lives Matter protestors. The account, featuring a Guy Fawkes mask as its profile photo, was used for years to keep tabs on the movements and plans of dozens of activists and was only exposed due to a lawsuit filed by the ACLU against the Memphis Police Department after several activists discovered they needed a police escort to enter City Hall.

The “evidence” gathered by the police officer posing as “Bob Smith” included a Facebook post by one activist recommending Sal Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals; the Facebook event page for a memorial for a 19-year-old killed by a Memphis police officer; and a post by a man in a private Facebook group saying he wanted to “hack” the Memphis zoo’s computer system after a conflict over parking. The flimsiness of the evidence collected speaks to the unwarranted nature of the surveillance.

An undercover officer wishes a protestor happy birthday

Screenshot: Legal filings (Blanchard et al. v. City of Memphis)

Memphis was among the police departments that did not send materials in response to the Freedom of Information request, saying for months that the request was “being reviewed.”

There are a few police departments that do have internal rules around covert social media monitoring. Police officers who want to do undercover Facebook stalking in places like Mountain View, Chicago, Minneapolis and Seattle, for example, have to get permission from a supervisor to create a covert account, and to keep logs of what they do with the accounts. When I described what happened in Everett’s case to the spokesperson for the Seattle Police Department, he was surprised by it.

“The whole purpose of working undercover is to work toward an investigative outcome,” said Sean Whitcomb, the public affairs officer for the Seattle Police Department, who has done undercover work in the past. “The work that we do has a focus. It’s not on a whim or just existing for the sake of data-mining. Otherwise you’re just waiting for someone to do something wrong and that’s not the point of undercover work.”

Terrance Everett was snared by what seems to be whimsical undercover work.

“Over three years of watching my page and they don’t see anything to arrest me until out of the blue I post something like that,” Everett told me over the phone from prison. “I got railroaded.”

Undercover Facebook cops are a new phenomenon born of the modern technological age, but the practice carries age-old risks of abuse of power. Steven Renderos of the Center for Media Justice sees the practice as another opportunity for discrimination and racial profiling. “The social media monitoring is being disproportionately targeted at people of color, and so social media use has harsher real world consequences for people of color,” he said by phone. “Fifteen years for posting a photo on Facebook… What exactly was the crime? People are being caught in trip wires. Low level crimes that shouldn’t have harsh consequences do and it’s leading to more people in prison and those people seem to be most often people of color.”

In her paper, Levinson-Waldman says covert online surveillance could be illegal if it’s discriminatory and if it could be proved that communities of color are being targeted, violating the Fourteenth Amendment, as was the case with the NYPD’s real world undercover surveillance of Muslim communities after 9/11. But it’s impossible to definitively prove that the overpolicing of communities of color is being replicated in the digital space unless law enforcement is forced to keep records of what they’re doing and make them available for review. At this point, that isn’t happening. Some police departments won’t even admit they’re doing this work, saying to do so would “reveal intelligence information.”

Social media is a useful and critical tool for police work, and police officers should certainly be using it for targeted investigations. But they shouldn’t be secretly friending people for indefinite amounts of time, keeping them under permanent suspicion.

For the Delaware police, Everett’s conviction was a win: They got a repeat criminal with access to a gun off the streets thanks to the posting of a stupid photo. But Everett’s experience should trouble us all. Everett’s stuck in a prison cell until his late 50s because an officer decided of his own accord to target Everett and surveil his digital movements for years, with no rules of the road and no warrant, waiting for him to screw up. That officer remains on the force and online, ostensibly secretly monitoring other individuals’ social network accounts, subject to no surveillance or oversight of his own.

Additional reporting by Anne Branigin and Erik Schelzig. Thank you to Jonathan Francis of the University of California Berkeley School of Law for FOIA help.

This post was produced by the Special Projects Desk of Gizmodo Media. Reach our team by phone, text, Signal, or WhatsApp at (917) 999-6143, email us at tips@gizmodomedia.com, or contact us securely using SecureDrop.