By David Steele, The Undefeated

Christina Chenault, a senior heptathlete at UCLA, has been operating a website for about two years called The Top Five. It began as a YouTube channel, evolved into a blog, and emerged as a platform for her fellow athletes to explore on-camera the needs, expectations, conflicts and pressures of big-time college sports.

Chenault cannot make money from it without putting her scholarship and eligibility in jeopardy. She, her guests and subjects have to be careful about the logos they wear, the sports they mention, even their shoes. And it doesn’t take a long visit to the site to see its value. For example, it features an early interview with gymnast Katelyn Ohashi, whose mesmerizing performance in January made her a viral celebrity.

“It’s interesting,’’ Chenault said. “It seems like the dialogue happens around everybody (in college sports) except other athletes.’’

“It” is the NCAA bylaw barring athletes from profiting off their names, images and likenesses (NILs). It prevents Ohashi, Chenault and every player in every sport at every level joining the schools, businesses and the NCAA cashing in on them.

And that, of course, includes athletes at historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs), which are far from the spotlight that falls on the UCLAs of the world, even in track and gymnastics.

The NCAA, pushed by new state laws following the one passed in California in September, says it will allow athletes’ NIL benefits no later than January 2021. When it does, it won’t be just the biggest names in the biggest revenue-producing sports who will be able to take advantage.

With the NCAA completely unyielding on actually sharing revenue with athletes, this door is the only one that players at North Carolina A&T and Alcorn State – to use Saturday’s Celebration Bowl opponents as one example – have available.

The students in the smallest sports with the least visibility and lightest public footprint will have the same opportunities as the ones in the big-time bowl games, as well as NCAA tournament basketball games.

It will benefit athletes who resemble Chenault more than the most rabid opponents of NIL benefits insist: “They said female athletes and non-revenue athletes never will be part of it, and I’m both,’’ she said. “I think if you position yourself well, you definitely can.’’

Thus, the football-and-basketball monopoly that defines the entire scope of big-time college sports won’t necessarily define which athletes get to tap into the newly-liberated marketplace. Those misperceptions are just as prevalent at HBCUs and other small, low-revenue programs in the NCAA. If you can monetize your name and fame, eventually the NCAA won’t be able to stop you from doing so.

Granted, said sports sociologist Richard Lapchick, HBCUs are low on the college sports money totem pole, and their athletes will likely benefit less from the new NIL rules than athletes at the major programs. But “We live in an entrepreneurial society, where people who have an opportunity to seize an opportunity, will seize the opportunity.”

So if a player with NFL or NBA potential lands at a Prairie View or Norfolk State and he blows up, he can be rewarded for it through NIL deals just as the all-Americans and Heisman candidates at bigger schools.

What HBCU athletes could have benefited?

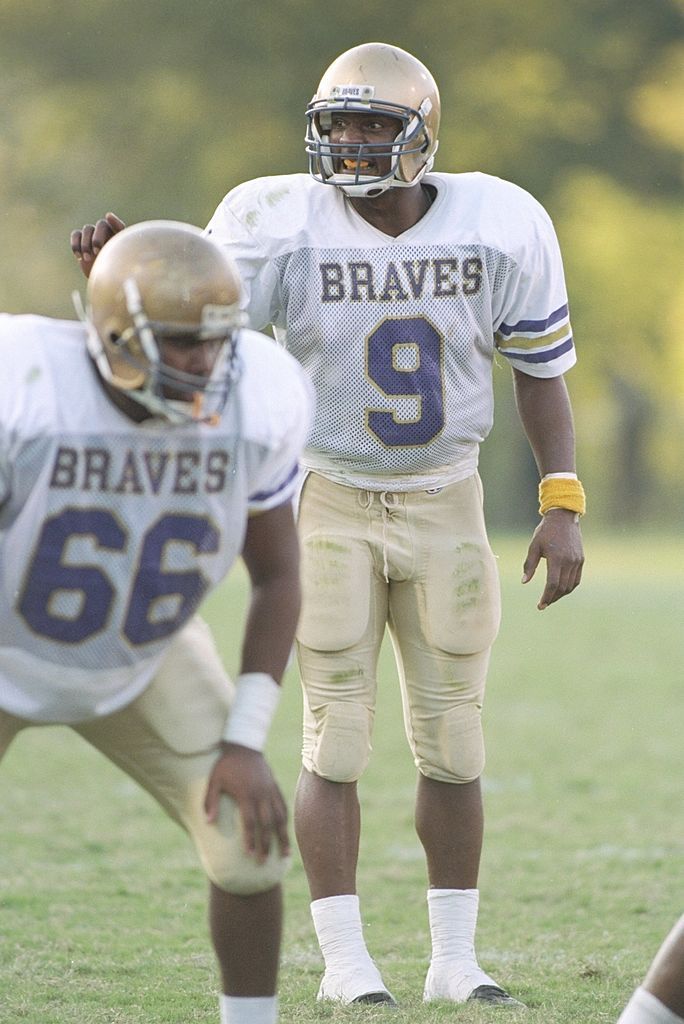

“If you go back to the days of Steve ‘Air’ McNair, he was on the cover of Sports Illustrated which was rare for a player from an HBCU back then, and he was third in the Heisman voting,’’ recalled Pep Hamilton, now the head coach of Washington, D.C.’s XFL franchise, and formerly quarterback and assistant coach at Howard University in their most recent run of success in the 1990s. Hamilton was preceded by future NFL draft pick and ESPN analyst Jay Walker, and followed by Ted White, who still holds the MEAC record for career passing yards.

“Think of the impact that had,’’ Hamilton said. “Heck yeah, the field can be equalized for players at HBCUs … To see HBCUs, and any players at the FCS level, have an opportunity to benefit in any way, it would be great for them. It would be great for any college kid.

“That was a special time for the university, and it would have been great to see the folks walking around the city with Jay ‘Sky’ Walker jerseys, and to see Ted ‘Sweet Feet’ White on a billboard on Georgia Avenue. The players would benefit, and the university would benefit.’’

Alcorn State

They wouldn’t even have to be nationally-renowned figures as a McNair, a Doug Williams or an Earl Monroe were decades ago – as Hamilton pointed out, fame within their circles and within their region would be good enough. One notable example tied to Saturday’s game: running back Tarik Cohen, who finished his career three years ago as the MEAC’s all-time leading rusher, played in the Celebration Bowl with North Carolina A&T and now stars for the Chicago Bears.

Nor do they have to be season-long or career-long recognition: one moment in a regular-season or postseason game can do it. Of the eight all-time March Madness upsets by 15-seeds, three were HBCUs (Coppin State in 1997, Hampton in 2001, Norfolk State in 2012). With the Celebration Bowl carried annually by ABC, such a moment could happen in that game with no prior notice.

While not an HBCU, this season’s shocking last-second win by Stephen F. Austin at top-ranked Duke illustrated how an NIL opportunity can appear in an instant: Bahamas-born Nathan Bain scored the game-winner and immediately saw a Go Fund Me page he had set up to help his family recover from Hurricane Dorian explode from some $2,000 before the game, to more than $150,000 less than 72 hours later.

It’s happening already in the NAIA

Ironically, all of the aforementioned athletes could have benefited, even if not directly monetarily, from a unique position in the national consciousness … had they not played at an NCAA institution. The NAIA has had a bylaw (Article VII Section B-8) allowing NIL benefits for athletes for several years, pointed out NAIA president Jim Carr. With restrictions on connecting the athlete to a specific school or their sport, athletes can remain eligible while capitalizing on their name.

Neeta Satam for The Undefeated

One in particular did: Toni Harris, one of the very few women who have ever played intercollegiate football, particularly as a non-kicker. Last year, when she was still in junior college, Toyota centered an ad around her unique story and ran it during the Super Bowl. When she signed with the Missouri’s Central Methodist University, she was eligible to play this season.

In her case, Carr said, “We did a good job in structuring the rule.’’ Yet, he said, he and the organization want to structure it even better – it underwent some loosening of restrictions at last year’s annual convention, and they plan to review it and likely loosen it further at the upcoming March convention.

“It just seems to us at our level – and I’m not speaking for the NCAA – that we should allow student-athletes to be treated the same way as every other student on campus.’’

The adjusting of the rules, Carr said, would affect its HBCUs as well which do not have the same financial and resource-related disparities as the ones in the NCAA divisions. The greater irony of the NAIA’s policy? All the HBCUs in the NCAA were once part of the NAIA before the NCAA allowed them in. Tennessee State’s basketball team was the first black college to be recognized as a national championship by an integrated governing body, when it won three straight NAIA tournaments from 1957 to ’59.

Current athletes who can capitalize on this revenue stream are not on the national radar now, but could be eventually.

At least two international sprinters from HBCUs made names for themselves at last spring’s NCAA outdoor championships: Ghana’s Joseph Amoah of Coppin State in the men’s 100 meters, and Jamaica’s Kiara Grant of Norfolk State in the women’s 100 meters. North Carolina A&T sprinter Kayla White, a Miami native, also finished strong at the NCAAs.

All have chances to compete for their nations at next summer’s Olympics in Tokyo. For now, none can capitalize on their fame, in the U.S., in their home countries or on their own campuses. Even if they are small opportunities, they are still something only future athletes can hope for.

Will anything really change?

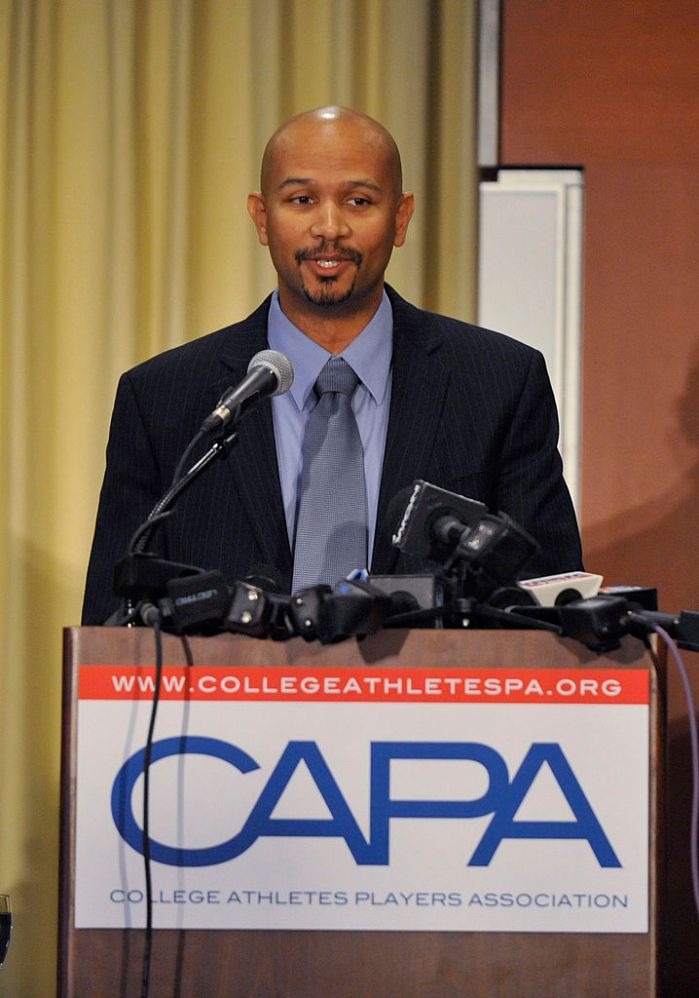

“With HBCUs, not much is gonna change. Might competitive equity change? No,’’ said Ramogi Huma, executive director of the National Collegiate Players Association and a former linebacker at UCLA.

Huma and his group were early advocates for college athletes’ equity in general and NIL benefits in particular, including the California law that allowed NILs and pushed the NCAA to change course. The closest HBCUs to California are more than 1,000 miles away, but the dominos are starting to fall in states that are homes to those schools.

“There was a major focus on schools that have less money, even if not specifically HBCUs, said Huma about the California’s Fair Pay to Play Act. “In California, they focused more on the public schools, as they should be, because they’re paid for by tax dollars. Focusing on schools that are broke was first and foremost; focusing on black students, as a civil-rights issue, was also first and foremost. That impact on other states was definitely seen as positive.’’

One strategy in the works for the NCAA to get ahead of the growing list of proposed state laws is going to Congress for federal legislation to govern NILs. NCAA president Mark Emmert reminded an audience for a Q&A session at the Aspen Institute in Washington this week that he has already solicited help from senators Mitt Romney and Chris Murphy.

In a panel discussion, though, Rep. Mark Walker of North Carolina – who in October co-sponsored a bipartisan House bill that would open the door for athletes’ NIL rights – said the NCAA shouldn’t quite hold its breath on congressional support. His example of whom his bill was aimed to help came from one of the schools playing in the marquee Celebration Bowl this weekend.

“The 1 percent, the Zion Williamsons, they’re gonna be just fine,’’ Walker said, “but the 99 percent who want to have access back in their hometown – if the backup quarterback at North Carolina A&T, the university I represent there in Greensboro, N.C., if he wants to go to his hometown and market his ability at a restaurant or something, get a couple of hundred dollars for signing autographs, he ought to damn well be able to have that opportunity.

“But the fact (is) that the NCAA says, ‘No, young man or young woman, whether you’re on the volleyball court or whatever, you can’t do that,’’’ Walker continued. “To say even those 99 percent cannot do what every other student, scholarship or not, has access to, it’s a travesty, and it certainly should be resolved sooner rather than later.’’

David Banks/Getty Images

Chenault, the UCLA track athlete, said that seeing her fellow athletes on campus relate to her site did not surprise her, but seeing athletes from other colleges facing the same problems and conflicts did. Including, she said, HBCU athletes.

“You can see the similarities and the differences at those levels, compared to what we see at UCLA – at (Division I), at Division III, where they don’t have money, where they do have money,’’ she said. It taught her something about the privilege she has at a school the size of UCLA, and gave perspective on how HBCU athletes and others navigate minefields like hers without the resources or recognition.

“I wanted to do a series on the debate on what if all black athletes just went to HBCUs,’’ Chenault said, adding that she still might.

But she would not be shocked if an HBCU athlete already has begun one or put together a venture like hers and, like her, cannot monetize it under the current rules.

It will not happen before her graduation this spring, or before the next possible NCAA tournament upset by an HBCU, or by the time the 2020 Summer Olympics finish.

But its time is coming, and for HBCU athletes, it’s long overdue.